Shapes and Sizes

I have a confession to make before you continue on in reading. It may change your desire to read, it may even change your opinion of me. I’m willing to take that risk. Ready. Here it is: “I love math”. Math makes me happy. There is a long list of things that I am unable to do, but math is not one of them.

Therefore, when I began reading D.W. Bebbington’s, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s, it gave me great pleasure when it introduced the four-sided distinctive markers of the evangelical movement with these words:

“There are four qualities that have been the special marks of Evangelical religion: conversionism, the belief that lives need to be changed; activism the expression of the gospel in effort; Biblicism, a particular regard for the Bible; and what may be called crucicentrism, a stress on the sacrifice of Christ on the cross. Together they form a quadrilateral of priorities that is the basis of Evangelicalism.” (p.2)

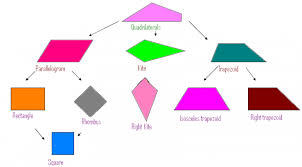

“A quadrilateral of priorities”, an awesome manner to describe this movement, of which I am but a small part! This picture of the four straight sides of evangelicalism helps me to understand more of my own role as well as the recapturing of British evangelical history. Based on this analogy, it might be too simple to presuppose that sometimes we try to construct our evangelical practice into rectangles, where the sides of conversionism and Biblicism are of equal (perhaps longer) lengths and where activism and crucicentrism form the shorter ends.

At other times we may tend toward trying to keep our evangelical practice within a square box, all four sides being equal. That too, places limits on the capacity of a quadrilateral to grow, adapt and adjust to the transformative effects of the culture.

However, as described in this writing, evangelicalism has been subject to a number of forces, which has influenced its changing shape through the years. In a manner that reminded me much of the poem (Priestly Duties by Stuart Henderson) read by Martin Percy at the Global Leadership Conference in London, UK, Bebbington identifies the reality of those influences, made more humourous because of their proximity to reality (p.11). The role of clergy within evangelicalism has tremendous responsibility, at times too great, and yet provides a tremendous opportunity beyond more liturgical roles. Given my calling to this same role, it was intriguing, humbling and alarming to trace the steps through the beginnings of British Evangelicalism relating through my current experiences.

Though designed to be quadrilaterals, there have been times when we have literally lost an edge, becoming triangular. The influence of wealth upon the church is depicted to have removed the value of crucicentrism from evangelical practice. Instead of sacrifice and dying to self there is a promotion of self, the preservation of comforts and the reinforcement of class differentiation:

“To appear at church was to court the contempt of neighbours for not being able to dress the family adequately. Nor could many families afford pennies for the offering. And one of the chief deterrents was the pew rent system. Most nineteenth-century places of worship, apart from older parish churches, were financed at least in part by hiring our particular pews to those who would pay for them. Grades of comfort dictated price differentials. Consequently variations in social status were imported into church. Cheap or free seating was normally made available for the poor, but often in inconvenient corners behind pillars.” (p.112)

At other times, the triangle was formed by a lack of activism (p.182), which deemed that the demonstration of social concern was not in keeping with the need to focus on conversionsim.

It may even be possible that being influenced in our times by the age of the large gatherings (i.e. Billy Graham Crusades) we have further devalued our capacity as evangelicals to simply conversionism and Biblicism (p.259). Trying as we might to keep our congregations functioning within two parallel lines, the resulting broad growth at the expense of a depth of growth seems inevitable.

Certainly in our current world, and the uniqueness of each global location, our roles as congregations and clergy will vary. However, those variables should only serve to transform our identity as quadrilateral forces of light in a world of darkness. The mistake we make is the attempt to hold on to old forms while ignoring the changing variables of society. The Church can still have an influence in our communities by retaining the A, B, Co and Cr of our God given design. I think this is what Bebbington was addressing as he spoke about the situation facing British Evangelicals at the end of the nineteenth century (p.272). It may seem easier to lead a linear, parallel or triangular church, but true leadership will seek to recapture the quadrilateral essence of our design and learn to make adjustments to the formula that our cultural contexts demand, knowing that each local context will have a different set of variables causing influence on the original design. Our shapes and sizes will differ, but our capacity to retain the straightness of our four sides shouldn’t. From a mathematical perspective that process is called a transformation. Transformation retains its original properties but adjusts according to variables imposed. Too often our current culture imposes a rigid shape and size upon us through books, conferences and “successful” models, when what is needed is the reminder that we are all given a four sided quadrilateral: conversionism, activism, biblicism and crucicentrism. Maybe it’s time to start training our leaders to apply some simple math so that they and their communities of faith can experience the wonder of transformation?

Transformation, isn’t that what we all want anyway, for ourselves, for our churches and for our communities?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.