Evolutionary Evangelicalism

I taught a course for a few years called “Religious Themes in American Culture.” This course caused students to think about the implications of the Christian faith in American cultural evolution. I talked often about the “Sacred/Secular Dance,” a concept that helped students see that the secular culture often has great impact on the Christian Church and that the beliefs and practices of the culture often have more influence on the Church than the Church has on the culture. We also studied contemporary ads, music, symbols, and other types of media and discovered that concepts in Christianity had found their way into American society as well. And, we watched a set of videos called Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory by Randall Balmer[1]. Balmer skillfully and objectively traces Evangelicalism in the American context with all its foibles, shortcomings, and positive contributions. What I attempted to do in this course, David Bebbington does for British Evangelicalism in his book, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain.[2]

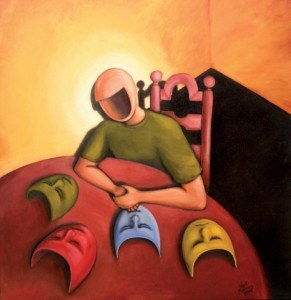

In his thought-provoking text, David Bebbington paints for his readers the history of evangelicalism (primarily in Britain) from the 1730s to the 1980s. His work kept me thinking of the word “change.” Then the word “evolution” was impressed on my mind – the evolution of thought, of beliefs, of interpretation of Scripture, and of cultural and social influences that shaped this branch of Christendom. This book is about change – about theological evolution. For Evangelicals there are four qualities that have marked the movement according to Bebbington: “Conversionism, the belief that lives need to be changed; activism, the experience of the gospel in effort; biblicism, a particular regard for the Bible; and what may be called crucientrism, a stress on the sacrifice of Christ on the cross. Together they form a quadrilateral of priorities that is the basis for Evangelicalism.”[3] In just under 300 pages Bebbington traces the changes of theological beliefs and practices of British Evangelicalism.

Both secular and spiritual movements influenced the thinking of Evangelicals in the eighteenth through twentieth centuries. These movements included The Enlightenment, Romanticism, the Holiness Movement, and the Charismatic Movement, to name a few. Evangelicals were active in the Church of England and in countless “dissenting” churches and denominations to one degree or another. They came from Calvinistic and Arminian theological perspectives. They were also involved in both conservative and liberal British politics. I was surprised and refreshed to read of the diversity of thought and behaviors of Evangelicals described by Bebbington. And, as time passed, so also passed many Evangelical leaders – to make way for new leadership, new interpretations of Scripture, different ways of relating to culture, to society, and to each other. It is no exaggeration to say that this was an evolutionary movement, never stagnant, never static. Its history has not been without controversy, without human error, or without critics; in fact, it is accurate to say the Evangelicalism is by nature a challenge to the status quo.

Besides Evangelical diversity, I also learned that Evangelical beliefs and behaviors are cyclical – they come and they go – then they come back again. The one example that I would like to focus on here is the teaching on the futurist premillennialism of J.N. Darby. After a season of a postmillennial understanding of eschatological events, Darby contributed a new Biblical interpretation to the Evangelicals of his day (the 1820s and 1830s). In the context of a new literal understanding of prophesy and eschatological events, Darby thickened the plot by emphasizing a literal “rapture” of the church before the 1000-year millennial period. Bebbington writes of Darby:

He steadily elaborated the view that the predictions of Revelation would be fulfilled after believers had been caught up to meet Christ in the air, the so-called ‘rapture’. No events in prophecy were to precede the rapture. In particular„ the period of judgments on Christendom expected by other premillennialists, “the great tribulation”, would take place only after the true church had been mysteriously translated to the skies. The second coming, in this view, was divided into two parts: the secret coming of Christ for his saints at the rapture; and the public coming with his saints to reign over the earth after the tribulation. Darby’s teaching was often termed ‘dispensationalism’ because it sharply distinguishes between different dispensations, or periods of divine dealings with mankind. Although never the unanimous view among Brethren, dispensationalism spread beyond their ranks and gradually became the most popular version of futurism. In the nineteenth century it remained a minority view among premillennialists, but this intense form of apocalyptic expectation was to achieve much greater salience in the twentieth.[4]

Darby’s doctrinal position received some acceptance, but this doctrine lay relatively dormant for almost a century, as Evangelicals dealt with more pressing issues. However, this teaching has had a significant impact on my life in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This “new doctrine” was introduced to me and to my family in my teens, over 40 years ago. These were the days of the Evangelical film, A Thief in the Night,[5] the music of Larry Norman[6] (I Wish We’d All Been Ready), and many popular books written by Hal Lindsey[7] on the subject of the “rapture” of the Church. Many young people came to Christ through this “new” Evangelical movement. Our family began attending a “Jesus Movement” church in California called Calvary Chapel of Costa Mesa. I eventually became a youth pastor at this mega church. Eventually, as described in our text, we began to take on a defensive posture (and sometimes an offensive posture) toward “the world.” Our pastor, Chuck Smith, figured out that Christ would probably return for his church in the early 1980s. Many people were swept up into this teaching. But the Lord did not come, at least physically. And many lives were damaged. There were so many disillusioned souls during this movement that many left the faith – or at least the Evangelical faith – once and for all. But some stayed faithful to the teaching of these Evangelical churches. Among the faithful was my father, who is now 81 years old. He is still a conservative, evangelical, fundamentalist Christian who holds firmly to a literal rapture of the church, which could come at any moment. His belief system has not changed in the last 40 years. I love my father. But we do not agree on many things, so our relationship is somewhat superficial. I accept this but I also mourn the relationship we could have had.

I came to faith at nine years of age in a Conservative Baptist Sunday School class. I could confidently say that on that day in 1965, my Sunday School teacher, Mr. Hansel, “scared the hell out of me.” But the fear turned into a genuine love for Christ and an eventual call to full-time ministry. In my years as a Christian and as a minister, I have experienced many different denominations: Conservative Baptist, Assembly of God, Foursquare, Calvary Chapel, Anglican, Presbyterian, Eastern Orthodox, Methodist, Roman Catholic, Several Community churches, Lutheran, and Episcopal. My experiences in these churches either reinforced or challenged my Evangelical roots. Add to this my educational endeavors in two Evangelical institutions of higher education – and now a third – and one might think that all of these experiences should have strengthened my Evangelical foundation. Actually, what all of these experiences have ultimately done for me was to shape me into a deeper thinker, a person who isn’t afraid to ask tough questions, and a person who is open to a broader (more liberal) understanding of religion and life. I have developed into the person I am today, with fewer spiritual answers and more spiritual questions. I cherish mystery more than certainty. And I have had to conclude that at this point in my life I am not an Evangelical. I am not against Evangelicalism; how can I be, it is my heritage. But I do not have the certainty I used to about Evangelical beliefs and practices, particularly about the rapture of the church. Nevertheless, I love Jesus and am in a community of Believers that I am committed to. My father doubts my salvation, disagrees with my politics, doesn’t think my church is “right on,” and detests my eschatology. But that is OK with me; it doesn’t change my love for him. And who knows, I just might be wrong. At this point in my life I would say that I am an evolving Evangelical. Thank you David Bebbington for the clarification!

[1] Randall Balmer, Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: Exploring the Amazing Vitality and Diversity of Evangelicalism and Its Role in American Life. [VHS] (Worcester, PA: Gateway Films/Vision Video, 1992)

[2] David Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1989)

[3] Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain. 2-3.

[4] Ibid., 86.

[5] Donald W. Thompson [Dir.] A Thief in the Night, [Film] (Mark IV Pictures Incorporated, 1972)

[6] Larry Norman was born on April 8, 1947 in Corpus Christi, Texas, USA as Larry David Norman. He was married to Pamela Norman and Sarah Norman. He died on February 24, 2008 in Salem, Oregon, USA.

[7] Hal Lindsey, born in 1929, is a dispensational preacher and “Christian Newscaster.” His website is http://www.hallindsey.com.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.