Who are our brethren?

Looking Back

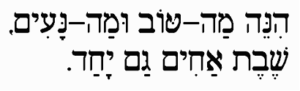

Reading about life in Israel and Palestine over the past 100+ years evoked some diverse emotions. Firstly, nostalgia as I was taken back to my college Hebrew classroom where we began each class by singing, “Hineh ma tov uma na’im Shevet achim gam Yachad.” How good it is for brethren to dwell in unity (Psalm 133:1). (I’ve posted a version of this song above.)

Secondly, something between resignation and despair. Despite their ties of “brotherhood” going all the way back to the story of Ismael and Isaac, the Palestinian and the Israeli people seem unlikely to dwell in unity anytime soon.

Before the events of October 7, 2023 (or more accurately before reading The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: A Very Short Introduction) I had a vague understanding rooted in childhood impressions and bits and pieces that I’d picked up over the years. I would say that my perception was not misinformed, just very surface-level and incomplete. I don’t know that I would have articulated it as such, but my impression was like there was a seemingly-eternal pendulum swinging between violent conflict and ongoing peace negotiations. Sometimes we would hear about outbreaks of violence or suicide bombers. Other times there were peace summits and church groups touring the Holy Lands. But eventually the pendulum would always swing back the other way.

Reading this book certainly deepened my understanding and broadened my historical knowledge of the situation. I appreciated learning about the roots of the conflict that go back to Ottomon Palestine and then transition to British-controlled Palestine after World War I and later to United Nations control after World War II. These were chronological details that definitely didn’t register in my brain before this week’s reading.

As I read and simultaneously sorted out this new information, I was especially struck by the introductory statement: “The ‘pressing and tangible’ aspect of the conflict is how to share the land.”[1] While the issues are complex and intricate, yes, the conflict comes down to how to share the land to which both peoples lay claim. History has revealed time and time again a sort of “fundamental colonial dynamic”[2] beginning with British rule[3] and subsequently in the Israeli approach deemed “conquest of land” and “conquest of labour.”[4] This has led to a seemingly endless cycle of violence and failed peace negotiations. In the early 2000’s the two-state solution seemed to be the way forward, notably with the UN’s recognition of the Palestinian state in 2012. Now, in light of the most recent conflict, the two-state solution is increasingly being called into question.

Looking Forward

One survey of Palestinians revealed that About 62 percent believe the two-state solution is no longer possible.[5] According to Samer Elchahabi of the Arab Center in Washington D.C., this is fundamentally because “the authority to define a Palestinian state has always rested with external powers, whether Israel, the United Kingdom, or the United States. This stems from a colonial legacy in which Palestinians are not included in the discussion about their fate, contradicting international principles of self-determination.”[6]

But what would the alternative look like? If we listen again to Elchahabi, he suggests moving “toward a model of shared citizenship and equal rights…. Israelis and Palestinians alike should imagine a unified state that upholds the rights and dignity of all its citizens, forging a shared identity from the rich tapestry of its diverse peoples. This vision, while challenging, holds the promise of a lasting peace built not on separation and segregation but on the foundations of justice and mutual respect.” It may seem idealistic to expect these two people groups to put aside their differences to form a functioning government. But we do have precedent in countries like Belgium and South Africa where multiple ethnic and linguistic groups unite to form a democratic government.

Further Musings as I Navigate the Current Reality

Before this post draws to a close, I want to consider two further areas to ponder. We have all been formed by the narratives to which we have been exposed, and this certainly holds true in how we view the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. If the language of colonialism is shocking to some, it is banal and taken for granted by others. As I grapple with the current war, I’m interested to see what parallels emerge later in the semester when we talk about colonialism and slavery in America’s history.

Secondly, I wonder what lessons we can learn for our own divided society, where coexisting peacefully often seems impossible. The Palestinian-Israeli conflict is ultimately an incredibly complicated situation with no viable solutions. There is no win-win resolution. There is no way forward that does not necessitate learning to coexist peacefully, and yet that is exactly what has been failing for generations. Looking at our own society, I fear we are headed down a similar path. What could we learn from the past 100+ years of conflict between Israel and Palestine about how to (or how NOT to) live in harmony with those who are different from us? How do we foster respect even when we disagree?

“Hineh ma tov uma na’im Shevet achim gam Yachad.” How good it is for brethren to dwell in unity (Psalm 133:1).

[1]Bunton, Martin. The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. Xii.

[2] https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/shifting-the-paradigm-the-one-state-solution-as-a-path-to-peace/

[3] Bunton, Martin. The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. 24.

[4] Ibid., 26-27.

[5] https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/05/approaching-peace-centering-rights-in-israel-palestine-conflict-resolution?lang=en

[6] https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/shifting-the-paradigm-the-one-state-solution-as-a-path-to-peace/

9 responses to “Who are our brethren?”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You put into words what I could not regarding the way I (and I would guess many evangelicals and probably others in our cohort) thought about Israel and the Middle East: an “eternal pendulum swinging between violent conflict and ongoing peace negotiations.” And, I was hoping to be on one of those “groups touring the Holy Lands,” not long ago with a group from the seminary where I teach from time to time, but that trip has still not happened.

I found Bunton’s historical overview to be super helpful (particularly the first part of the book), and for me he filled in some gaps I was obviously missing.

I would be curious to know how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict gets discussed in and around your city in France, or if the subject even comes up at all (I’m guessing it does?).

There is some discussion around the events of October 7th and since, but mostly ongoing protests/marches in support of Palestine. The city has a Muslim population of roughly 25% so it’s not surprising that there’s quite a bit of attention paid to the ongoing conflict. Although, for what it’s worth, it doesn’t seem to be affecting daily life nearly as much as the Ukraine war, I think because Ukraine feels a lot closer geographically than Israel and Palestine.

Hi Kim,

Alas, the pain and blood on both sides do not speak to a quick resolution. Forgiveness, will take centuries and perhaps will never come.

One of my critiques of this book and others of its time is the lack of depth in religious perspective.

I would have liked more….

Islamic Perspective

Though the question asks for a biblical view, it’s important to note the Islamic perspective as well, given the significant Muslim population among Palestinians.

“Allah the Almighty has not used the word “يَمْلِکھَا” [in the aforementioned verse] but in fact said “يَرِثُھَا”. This manifestly shows that the true heirs [of Palestine] will always be Muslims, and if it goes into the hands of some else at some point, such a possession would be similar to a scenario in which the mortgagor gives temporary control of their property to the mortgagee. This is the glory of Divine revelation, [and it shall surely come to pass].” (Al Hakam, 10 November 1902, p. 7)

Quran 17:1: Reference to the Night Journey of the Prophet Muhammad to Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. [Holy Land: The Quran also recognizes the land as sacred and significant, particularly to the prophets who are also revered in Islam.]

Jenney Dooley reminded me that Fukuyama’s “Identity” is rooted in religion and this book avoids relevant religious commentary.

What can we effect? Practically nothing on a human level. On a spiritual level, we have the power of prayer for both this crisis and the crisis in Ukraine.

Shalom…

Russ, you make a really important point that I didn’t know. From a Palestinian perspective, the conflict is also about more than just ancestral land. Muslims also feel they have a divinely-given right to the land. Have you read the book “Impossible Conversations” yet? One of my (grossly oversimplified) take-aways from that book is that when religion gets involved, you’re not going to change anyone’s mind. As you say, on a human level, it’s hard to imagine a peaceful resolution to this conflict.

Alas, a “Wicked Problem.”

My time in Ukraine helped me put conflicts into perspective. How much emotional capital do I invest in it? I have begun to ask the question, how can I expand the Kingdom in these chaotic times.

I have decided that while my heart goes to those who are suffering in the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, the BEST thing I can do is actively pray for them.

In Ukraine, however, I can be involved in the programs that work with orphans, widows and the internally displaced (Deut 10:18) and with the 300 children/25 coaches of the Penuel Futball Club in Kryvyi Rih. Additionally, developing a sports therapy program that ministers to wounded Ukrainian soldiers.

Like yourself I am will invest my emotional, spiritual and physical capital in the people God has called me to.

Shalom…

Kim,

How different the world would be if two people groups put aside their differences with a common goal to live in peace, mutually respect, and brotherly love? It requires laying down entitlement, pride, and doing nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. But rather, in humility valuing others above ourselves. (Philippians 2:3). A challenge for people groups of all kinds.

Well said. To take it a bit further, real peace would seem to require that everyone give up some of their own rights for the greater good- in service to a group of “brethren” that goes beyond Jew or Palestinian identities to image bearers. That is not a practice often seen in our self-centered world.

Hi Kim,

Thank you for sharing the video clip. It took me back to my Hebrew class as well. We didn’t sing but we did recite the Shema. As I read the book, I kept thinking about our time in South Africa and learning how injustices were handled following Apartheid in which the Truth and Reconciliation Commission allowed for the telling of stories. I hope that is possible some day.

Hi Kim!

Your critical questions challenge me to think about the same thing. That’s brilliant, Kim! I appreciate it.

Peace between the two countries seems like a futile and impossible thing to talk about. However, if we look at past examples of countries that were in conflict and have now made peace, it seems like peace is possible.

Mandela, whom I quoted in my writing, is a living example of a man who truly applied the teachings of the Bible and Christ about love and forgiveness without being driven by the desire for revenge. It is possible. We as a whole can achieve and bring about peace.