What Would Bring You Peace

“I can’t believe I am here again!”

“I can’t believe I am here again!”

I stared across the Holy City of Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives. This special and remarkable place that I had visited now three times, forever etched in my mind, and a place I think of longingly almost every day I’m away. Below me the white sepulchers of the Mount of Olives are staunchly contrasted with the green olive trees of the Garden of Gethsemane. And between them, a road.

As we walk, we sing, “Hosanna, Hosanna” just like the crowd did on the Palm Sunday when Jesus came to Jerusalem as King. It is always the first stop when I lead trips to Jerusalem and the best way to enter the “City of Peace.”

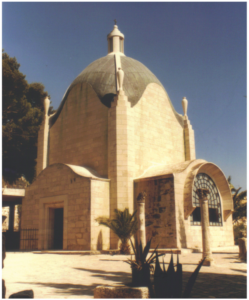

But rejoicing quickly turns to a different emotion as you enter the gates of a church called, “Dominus Flevit” or “Jesus Wept”. This church commemorates the spot where Jesus got off of his donkey and wept over the city of Jerusalem. As he is weeping in Luke’s Gospel, he says, “If you, even you, had only known on this day what would bring you peace—but now it is hidden from your eyes.”[1] Jesus, God of the Universe, Messiah and King had come to bring people true peace, but they were going to reject Him, ridicule Him and crucify Him.

On this particular trip, as we stopped and pondered this moment in Scriptures, the Muslim call to prayer came over the air from the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount where the Jewish temple once stood. On the other side of the temple mount, Jews pray day and night at the Western Wall of the temple, the closest place they are allowed to get to the Holy of Holies that once housed the very presence of God. I found myself, on this particular trip, also weeping for the city of Jerusalem and for those that have sought peace in anything other than Jesus and His redemptive work on the cross.

The complexity of Israel and Palestine, its history, its bloodshed and heartache and the continual question of how to bring peace in the part of the world has always been something that I’ve tried my best to understand every time I go to Israel by listening to those who call this place their home: Jewish Israelis, Arab Israelis, Messianic Jewish Israelis, Palestinian Muslims, Palestinian Christians. Each of them has a strong opinion about how to bring peace, each of them a different pathway forward. This complexity humbles me and has always brought me to my knees to pray for peace in the precious part of the world.

Martin Bunton’s book has helped me fill in some of the different gaps in history that I have read before, but not remembered. I will confess I was a little surprised at Bunton’s assertion in his introduction that, “weariness…has reinforced an ahistorical notion of the conflict as an ancient and religious one. The main challenge to resolving the conflict is essentially one of drawing borders.”[2] This claim that the complex conflict between Palestine and Israel is simply about the drawing of borders feels overly simplistic to me, because he sees land from an empirically western mindset. The problem with this, in my opinion, is that this is not how the Land is described to me by the people I have listened to in Israel and Palestine. Land is religious. Land is a birthright. Land is ancient. It is about more than drawing borders. It is deeper than a simple modern state or two state solution.

But while I disagree with Bunton’s perspective on this, it was very helpful to see how some of the historical engagement with the founding of the current nation of Israel has contributed to the complex situations of today. For example, Bunton aptly observes that, during the time of British rule in the 1930s, “what was unique in Palestine was the general failure to draw it cohabiting populations into basic mechanisms of government, such as a legislative assembly…The failure to create a legislative council in Palestine represents a key turning point in the country’s history.”[3]

This short history will be a helpful resource that I can continue to come back to for information on the different periods of modern history that have shaped the current conflict.

A month or so after the atrocities of October 7th, I noticed how social media had careened into the virtue signaling it often does around the war in Gaza. I saw posts that said, “I stand with Israel!” or “I stand with Palestine!” As a pastor, I’ve wrestled with how to preach and engage on political and cultural hot button issues from the pulpit. One of the challenges of engaging in these issues in our present age is that we want simple responses and simple answers to complex questions. Also, we are often looking for pastors and leaders to affirm the way we’re already thinking about something, rather than challenging us to think deeper about whatever issues we are being faced with. But on one Sunday during a message, led by the Holy Spirit, I took a few minutes before the sermon I was planning to preach, to invite our church into three things as a response to what was unfolding in Israel and Gaza, and these are the three ways I’m continuing to encourage our church to practice in light of the ongoing conflict in this region of the world.

The first invitation was to “Stand with Jesus”. In Joshua 5 an Angel of the LORD appears to Joshua before the city of Jericho falls and Joshua asks the messenger, ““Are you for us or for our enemies?”” The messenger replied, ““Neither…but as commander of the army of the Lord I have now come.”[4]

While it can be tempting to take sides between Israel and Palestine, or other complex issues where they seem to be two opposing parties, it is important to remember that Jesus doesn’t take sides in this way. Instead, Jesus stands with the hurting and the broken on all sides. He weeps with those who weep and mourns with those who mourn, and calls us to do the same[5]. When we stand with Jesus, we avoid the pitfalls of “us vs. them” thinking that is so prevalent in our world, but such a cancer to the kingdom of God.

The second thing I invited our church to do was to “pray for the church in that region”. I reminded them that we have sisters and brothers in Palestine, in Gaza, Israel, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, Syria. God is raising up His church in that reason and they need our prayer to be faithful witnesses in this present crisis. The purpose of this is to remember that the body of Christ transcends national borders, ethnic identities or political affiliations and creates a Family of God that is bigger, broader and stronger than any of the categories the world and its value system wants to work with.

The third thing I invited our church to do was to “remember the cross”. The cross is where God showed us what true power really is. The cross is where God showed us how we love our enemies and the cross is where God disarmed the powers of violence and evil and, in the death of Jesus, disarmed even sin and death themselves. In Revelation 12 we’re told that God’s people triumphed over the Accuser, “by the blood of the Lamb and by the word of their testimony; they did not love their lives so much as to shrink from death.”[6] My invitation to our church, and challenge to myself, is to remember that it will not be with weapons of war that ultimate peace will be obtained but instead with sacrifice, forgiveness and cruciform love. This might seem naïve or overly simplistic. I recognize the pain and destruction that has been caused is tremendous. But I believe that the Cross of Christ has the power to overcome the deepest divisions of our world, so it must be possible in this crisis in this part of the world God loves and died for.

This week the Patriarchs and Heads of Churches in Jerusalem released a statement calling for warring parties to end the bloodshed and the violence. Together they call on, “Christians around the world to promote a vision of life and peace throughout our war-torn region” and to “recommit ourselves towards working and praying together in the hope that, by the grace of the Almighty, we might begin to realize this sacred vision of peace among all God’s children.”[7] May it be so in me. May it be so in us. May it be so it the Holy Land.

[1] Luke 19:42, NIV

[2][2] Bunton, Martin. The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: A Very Short Introduction, Xii.

[3] Bunton, 25.

[4] Joshua 5:13-14, NIV.

[5] Romans 12:15, NIV.

[6] Revelation 12:11, NIV.

13 responses to “What Would Bring You Peace”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Ryan, I am a bit envious of your three trips to the region. I have been there once and it was a significant experience. It changed the way I read and preached the Scriptures. Just thought I would throw that in there.

I appreciate the way you described your pastoral leadership on a very thorny issue. It is certainly easy to get drawn into taking sides but you managed to help your congregation turn their eyes and hearts toward Jesus. Thanks for that.

Sometimes, though, in an attempt not to be divisive, we tend to not stand for righteousness and justice at all. I’ve been memorizing the beatitudes and have been reflecting on “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.” This right alongside those who are meek and the peacemakers. How might we address the wrong without polarizing people?

Hey Graham! Thanks for your response and question. I think the first place we’re called to hunger for righteousness and justice is within ourselves, to take the “plank out of our own eye”. Then, I think we look at righteousness and justice for the oppressed and those on the margins, regardless of nationality or ethnicity. I think this current conflict has oppression and heartache in every corner of Israel and Gaza, my God bring peace to Jerusalem

Hi Ryan, When I first started reading your post my mind went to, yes, there are a lot of historically faith based reasons why the land is important to so many groups. I started wondering if the leaders of the different countries or groups were fighting for their right to exercise their faith in the holy area or was it power, greed, and ego. Yet, as I continued reading how you led your congregation to call on Jesus it became evident that those other reasons don’t matter. What really does matter is our responses in relation to the Lordship of the one true King, Jesus.

I know that not every sermon is about the congrgation “liking” it, but did you get any feedback from your congregation the hinted that they are beginning to wrestle with the topic?

Thanks Diane! The feedback I got from my ‘mini-sermon’ was positive and people said it was refreshing to hear a proposed middle way in the midst of all of the either-or thinking they had been bombarded with.

Thank you Ryan, great post. I appreciate how you point out that Bunton is not looking at the conflict in any religious way at all. Isn’t it interesting how the removal of Jesus from the challenges of being human makes everything so much more difficult?

I also appreciate your invitations to your congregation. How did they respond to your message and questions?

Hi Debbie. Overall it was a positive response. We have a congregation that generally wants to think deeper about issues that what is presented to them on social media or either/or thinking. I am grateful for that. We don’t always have great feedback loops for further discourse on issues like this, but are exploring how to do that better in the future.

Ryan,

A year ago or so I began to think about land from a different perspective. I began to underline the word in a different color every time I find it in Scripture. Just this morning as I read in Jeremiah I was reminded of how God does look at land in different ways than we do. Jeremiah writes how the land is mourning and will become desolate, a wilderness that it uninhabitable. This is in contrast to the Garden narrative. I appreciate your challenge to your church, it is through the cross that we will get back to the Garden and the land will no longer be a desolate wilderness.

Thanks for this reflection, Adam. All creation is indeed groaning for redemption and restoration of God’s image-bearers.

Hey Adam! Thanks for your reflection. As someone who has visited Israel for other purposes, I hope to finally take the religious tour to deepen my spiritual formation. I appreciate your perspective on how land is viewed and how that cannot be overlooked. Do you think many people are in the dark about this and tend to focus on the other factors?

Hi Ryan,

Thank you for your post. I especially appreciate your approach of guiding your congregation to respond thoughtfully and spiritually. It is clear that you are striving to provide a new perspective amidst the often polarized discussions about Israel and Gaza.

How would you encourage other pastors and church leaders effectively guide their congregations to engage with complex political and cultural issues, such as the conflict in Gaza, in a way that encourages deeper reflection rather than simplistic responses or virtue signaling?

Your post has encouraged me to recommit to praying for this part of the World. Thank you, Ryan!

Hi Ryan,

My first trip to Israel was in 2014. I remember catching a cold and having a lot of trouble sleeping. One morning in Jerusalem, I went to the hotel’s patio that overlooked the city after a terrible night of sleep. I was alone. There was no sight of the sunrise yet, and all was peaceful. At this moment, I could imagine Jesus looking over the city and saying, “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the prophets and stone those sent to you, how often I have longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, and you were not willing (Matt. 23:37 [NIV]).” So often, we are unwilling to accept the peace Jesus wants to offer us.

In his book, Bunton briefly makes reference to ‘psychological barriers’ regarding the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and the inability to reconcile. As you have grown as a follower of Jesus and a pastor, what ‘psychological barriers’ have been torn down for you personally concerning the Palestinian-Israeli conflict?

Hi Ryan, I always appreciate your posts!

You said that you disagreed with Bunton’s assertion that the conflict isn’t a religion one but one over land.

I was so surprised when I learned that the land Israel negotiated for didn’t include key historical and Biblical sites.

The disconnect I found is that I had always understood this to be a religious war, and there was a sense that Israel had the rights to the land due to the ancient Biblical history.

So I was surprised that the land didn’t originally include the Biblical sites. Had you already known this, or were you also surprised by this?