The Great Transformation

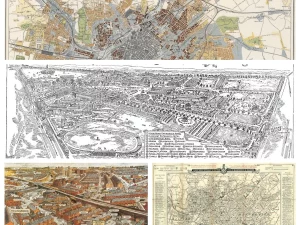

(Image – Maps of Industrial Manchester)

Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation, the political and economic origins of our time,[1] first published in 1944, is a seminal work offering an analysis of the economic and social upheavals that accompanied the rise of market capitalism. It is not a natural go-to book for me, but it was helpful in creating an understanding of the development of a self-regulating market economy in the 19th century. I will attempt to critique the book and finish with why non-economists should read the book and why they may find it difficult.

The book has been lauded for its intellectual depth and interdisciplinary approach. In his book Everything for Sale: The Virtues and Limits of Markets,[2] Political economist Robert Kuttner draws heavily on Polanyi’s framework, praising The Great Transformation for its depth in explaining how unregulated markets can lead to societal dislocation and economic instability. Fred Block, a sociologist (who also wrote the new introduction to the 2001 reprint), praises Polanyi for his penetrating critique of the classical economic assumptions and the concept of the self-regulating market. He has referred to Polanyi’s work as intellectually rich and transformative in terms of social theory.[3]Meanwhile, Political Theorist Nancy Fraser has engaged with Polanyi’s theories in the context of her own work on capitalism and social justice, commending Polanyi for his in-depth analysis of the “double movement” — the oscillation between market expansion and social protection, which she considers crucial for contemporary debates on social democracy and neoliberalism.[4]

One of the most interesting aspects of The Great Transformation is its historical analysis. Polanyi provides a detailed account of the economic changes in 19th-century Britain, illustrating how the rise of market economies eroded traditional forms of social organisation. I live in Manchester and have witnessed first-hand the effects of this moment in history. As the global epicentre of the Industrial Revolution, Manchester has had to work hard to rebound after the post-Industrial Revolution changes to become a thriving powerhouse[5] again in the Northern part of England. Polanyi focuses on how the commodification of land, labour, and money led to significant social dislocation, as communities that once governed these aspects of life through embedded social norms were now forced to adapt to the abstract principles of the market. Polanyi’s emphasis on the embeddedness of economic systems—that economies are always enmeshed within broader social relations—challenged the orthodox view of economics as a separate and self-contained sphere.

Polanyi’s central thesis—that the self-regulating market was an unprecedented and radical break from the past may be overstated. Critics have argued that his portrayal of pre-capitalist societies as harmonious and stable is overly romanticised. For example, his depiction of traditional economies as fundamentally non-market in nature does not consider the diversity of economic arrangements throughout history, including various forms of market exchange in pre-modern societies.[6] While Polanyi acknowledges the existence of markets in the past, his argument that the 19th-century market economy marked a qualitative transformation lacks nuance, making it seem as if all previous forms of exchange were benign compared to the disruptive force of modern capitalism.[7] Additionally, he underplays the coercive elements present in pre-capitalist societies and how power dynamics shaped their economic practices.

Critics of Polanyi’s concept of the “double movement” suggest it is ambiguous. He describes it as a tension between the expansion of market mechanisms and society’s attempt to protect itself through various forms of regulation and social intervention.[8] While this idea captures the reactive nature of social policy to economic change, Polanyi does not seem to provide a clear framework for understanding why some protective measures succeed while others fail. The concept of the double movement also seems to oversimplify the complexities of political struggle, reducing them to a one-dimensional opposition between market forces and social resistance. This perspective ignores the role of diverse interest groups, power dynamics within the state, and international factors that shape how societies respond to market disruptions, making it potentially insufficient for capturing the full scope of economic and political transformations.

The Great Transformation is worth reading for non-economists because it offers an interesting historical and social analysis of how market economies evolved, explaining the deep impacts of economic changes on society and politics. Polanyi’s insights into the tension between free markets and social stability resonate beyond economics, making it helpful for understanding the roots of modern societal issues, the role of institutions, and the balance between economic forces and human values.

Non-economists might find The Great Transformation challenging due to its theoretical concepts, historical references, and complex analysis of economic systems. Polanyi integrates economic, political, and sociological perspectives, requiring readers to navigate interdisciplinary arguments. Additionally, the book uses technical language and assumes familiarity with 19th-century European history, making it difficult for those without a background in these areas to grasp its nuances and broader implications fully.

I reluctantly read the book, grudgingly wrote a blog, and will happily pass the book on to some unsuspecting individual.

[1] Polanyi, Karl. 2001. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. 2nd edition. Boston, Mass: Beacon Press.

[2] Kuttner, Robert. 1999. Everything for Sale: The Virtues and Limits of Markets. Reprint edition. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press.

[3] Polanyi, xxvvii.

[4] Sadami, Arthur, and Mateus Bernardes dos Santos. “When Polanyi Met Competition Policy: Market Fundamentalism, Crisis, and Reform in the 21ST Century.” Journal of Competition Law & Economics, September 11, 2024, nhae013. https://doi.org/10.1093/joclec/nhae013.

[5] HM Treasury. 2016. “Northern Powerhouse Strategy.” Gov.Uk. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/northern-powerhouse-strategy.

[6] Samur, Tuğberk. 2022. “Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation: The Critique of Liberalism and the Emergence of Illiberalism.” Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.illiberalism.org/karl-polanyis-the-great-transformation-the-critique-of-liberalism-and-the-emergence-of-illiberalism/.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Polanyi, 79.

10 responses to “The Great Transformation”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hi Glyn, thank you for your post.

What would you add to improve the following statement based on the fact that “Polanyi’s …. lacks nuance …?”

“While Polanyi acknowledges the existence of markets in the past, his argument that the 19th-century market economy marked a qualitative transformation lacks nuance, making it seem as if all previous forms of exchange were benign compared to the disruptive force of modern capitalism.”

Hi Shela. Thanks. I think Polanyi’s perspective overlooks the complexity of pre-capitalist economies, where forms of coercion, inequality, and market-like exchanges existed, challenging the sharp distinction he draws between pre-modern and modern economic systems.

Thanks for your great work on this challenging book Glynn. How was the Church in Manchester impacted by the social upheaval and economic forces, and how has that impacted how you minister there today?

Hey Ryan. Manchester was the global epicentre of the Industrial Revolution. Mark Twain once famously said “I don’t need to go to hell, I’ve been to Manchester and it’s pretty close.” Manchester had magnificent wealth and absolute poverty with children in slave labour.

When times changed, the loss of jobs and infrastructure left the city with a gaping hole and increasing poverty. The city has completely reinvented itself since. However the poverty mentality is pervasive in the mentality of many on the city to this day. We face that daily. Preaching the gospel as good news matched with redemption lift is an important part of what we do.

HI Glyn, given the current economic conditions in Manchester and assuming it continues on its current path, how might it look in the next 50 years? Do you think the market will self-correct or will the poverty issues continue to grow?

Hey Jennifer, thanks for posting the question. While an economist may answer with mechanisms contained within economics itself, as a pastor and aspiring theologian, I believe that man-made measures for self correction, while seemingly effective, are temporal.

There will undoubtedly be moments of self correction, which will ease matters in different seasons. However, even Jesus acknowledged the truth that “the poor you will always have with you” (Mark 14:7). The words of Jesus should not excuse us from our responsibility for serving the poor and elevating them. In fact, Jim Wallace’s Bible (The Poverty and Justice Bible) that you graciously bought for us, highlights so effectively, what one the principal foci of the gospel is, ministering to the pool? The only true way to have a long-lasting break from these issues is when the heart of humankind changes. Perhaps revival is the best answer for this.

Glyn, I purposely selected your article to read because I expected you to give me some wise and perceptive understanding that I had missed. So I laughed out loud when I read you last sentence! 🙂

And I did: you presented me with some critiques of Polanyi.

What do you think the church can learn or implement from Polanyi’s message? Why does it matter to us as Christian leaders?

Haha Hi Debbie. I wondered if people would make it to the end of the blog and read the last line Congratulations, you win the prize, I’ll send you the book by Polanyi in the post 👏👏.

In answer to your questions; Firstly it’s pretty important for the church to know about the social impact of unregulated markets, recognising the importance of protecting community welfare. We have been doing this in church, without realising it for what it is. There is a government benefit that is given to churches in the UK called gift aid. This means that when a taxpayer gives money to the church or any charity, the government gives 25p for every 1 pound also. Many charities have been relying on this 25p in the pound from the government to expand the charitable work. We however approximately eight years ago took the measure that is 25p from the government was not going to be a necessary part of our budget for church ministry and use it as surplus to requirement. In fact, we are protecting yourself from the moment when the government may either reduce the gift aid or abolish it totally.

For church leaders, Polanyi’s work highlights the need to advocate for balance between economic forces and human dignity, building resilience and compassion within vulnerable communities.

Glyn, I appreciate your engagement with Polanyi and agree with your view on its relevance for those outside of economics. Considering your insights into the complexities and critiques of Polanyi’s ‘double movement,’ how do you think contemporary societies can effectively navigate the tension between market expansion and social protection, especially in the context of globalization and technological change?

Hey Chad. Responding as a pastor, as we navigate rapid market and technological changes, we must remember God’s call in Proverbs 31:8-9 to “speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves” and uphold justice. Our economic choices should honour the dignity of all. Balancing growth with protection for vulnerable communities reflects Jesus’ compassion in Matthew 25:40, “Whatever you did for one of the least of these…you did for me.” From a practical perspective our theology should underpin our practice.

Sadly, I think there will always be the greed of “those at the top” who seek to increase the gap between the rich and the poor. For example, when we look at how many hours we go to school how much is that is actually spent on teaching economics? It seems that the rich write the syllabus to keep the poor poor. Perhaps teaching children from infancy all the way through to high school and college on economics will be the best way to navigate attention.