Responsibility, Empathy, Compassion and Staying Differentiated

This week, I read Friedman’s classic work, Failure of Nerve. He presents differentiation as the solution to the problem: “America is stuck in the rut of trying harder and harder without obtaining significantly new results.” [1] The book’s theme is that differentiated leadership provides stability in anxious times, refuses to blame others, and sets new directions for systems. The differentiated leader provides a non-anxious, well-principled presence.

Friedman defines differentiation as “the lifelong process of striving to keep one’s being in balance through the reciprocal process of external and internal processes of self-definition and self-regulation.” [2] Differentiation is understanding where I end and where people around me begin and regulating my responses. I see and resonate with the need for a non-anxious, well-principled presence in our world today. I have one issue with the book – his take on empathy.

In my work with people in recovery, co-dependence is a significant issue. We can understand co-dependence through Friedman’s differentiation; co-dependency extends my self-definition to another person. The co-dependent person blurs the line between where they end and the other begins.

Friedman writes what he calls the “fallacy of empathy.” [3] Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. Friedman never defines empathy outright; he writes around it, showing its etymology and usage. The closest he comes to a definition is “to feel in.” [4] He connects an early definition of empathy for artwork: placing yourself in the art to understand it.

Friedman’s position is that as our empathy, our ability to feel in others, increases, our differentiation is at risk of becoming unregulated. To put ourselves in another person, as with artwork, risks blurring the line between where I end and another begins. Empathy, for Friedman, is connected with the idea of co-dependency, whereby by being empathetic, we extend ourselves or allow others to extend themselves into us. The ‘fallacy of empathy’ for Friedman is that we deprive people of responsibility when we are empathetic. He says, “on the most fundamental level, this chapter (on empathy and responsibility) is about the struggle between good and evil, between life and death, between what is destructive and what is creative, between dependency and responsibility…” [5]

Friedman passed away before finishing this work; I want to extend grace, recognizing he could have expanded on these ideas.

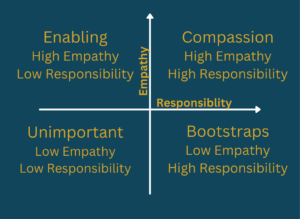

Friedman never says but impresses that empathy and responsibility are opposites on the same spectrum. As one rises, the other falls. He says, “The great myth here is that feeling deeply for others increases their ability to mature and survive…” [6] I want to reject this premise and say that we need both; people will thrive through others’ empathy and personal responsibility. Following Andy Crouch and his work Strong and Weak, we can be low or high in empathy and simultaneously be low or high in individual responsibility. That gives us this chart here:

The line for Friedman seems to run through Enabling to Bootstraps. He tries to avoid enabling, rightfully so, but he ends up in an equally unhelpful position.

Unimportant

When we treat people with low empathy and responsibility, we feel little for them and offer little to them. They are unimportant in our lives. Most of the people we pass on the street are unimportant to us. We have both low responsibility and low empathy for them.

Enabling

Some people use empathy toward them as a tool for manipulation and use our resources to enable their ongoing destructive behavior. When families of people with addiction continue to recognize the lies and still give the addict a degree of responsibility over their lives, they are enabling them to continue unhealthy behaviors. Our empathy is high, and our ability to ask them to take responsibility and our personal responsibility is compromised. Friedman recognizes this pattern and rightfully desires to avoid it.

Bootstraps

I don’t believe Friedman intended to land here, but he often does. In his favor, he states a deep need for leaders to care for their people. At the same time, he writes about people lacking self-regulation being destructive and that “empathy is also irrelevant to, and often distracting from, the resources that go into survival.” [7] Friedman says the survival of the host, family, or nation depends on limiting the “invasiveness of its viral or malignant components.” [8]

People – Friedman is talking about people as invasive, viral, and malignant. There are two problems with this approach. One, it treats the image of God abhorrently. Two, it provides no way out. Even if somebody were willing to work towards growth, when we lack empathy, we push all the responsibility for growth onto that person. Pull yourself up by your bootstraps. That ignores the fact that my growth comes from others giving themselves for me.

Compassion

In Matthew 14:14, Jesus, looking at the crowd, was moved to compassion. Σπλαγχνίζομαι (splanchnitzomai) is the Greek word for compassion, coming from splanchnos, guts. Jesus felt a gut punch looking at the crowd. He moved to cure the sick. Jesus, following the news of John’s death, has withdrawn from the people. They search him out anyway. They exhibit every characteristic of co-dependence and lack self-regulation. Jesus feeds the five thousand, anyway.

Friedman writes about “the irrelevance of empathy in the face of un-self-regulating organisms that are by nature always invasive and cannot learn from their experience.” [9] Scripturally, Peter tells us to be συμπαθής (sympathes) in 1 Peter 3:8. The Lexham Research Lexicon defines συμπαθής as “sharing the feelings of others; especially feelings of sorrow or anguish.” [10] συμπαθής is closer to empathy than sympathy. Empathy is a Biblical command. I want to be a differentiated leader who provides a non-anxious, well-principled presence and empathizes with the people around me.

[1] Edwin H. Friedman, A Failure of Nerve, Revised Edition: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, Revised Edition (New York: Church Publishing, 2017), 3.

[2] Friedman, 194.

[3] Friedman, 141.

[4] Friedman, 145.

[5] Friedman, 143.

[6] Friedman, 143.

[7] Friedman, 160.

[8] Friedman, 160.

[9] Friedman, 166.

[10] Rick Brannan, ed., Lexham Research Lexicon of the Greek New Testament, Lexham Research Lexicons (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2020).

4 responses to “Responsibility, Empathy, Compassion and Staying Differentiated”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Robert,

Thank you for the pictorial that breaks down the four quadrants. That is very helpful, as I have been trying to digest how we can differentiate and be connected without being superficial and indifferent. Do you think Friedman lands, intentional or not, in the “Boot Strap” section because it is the cleanest area to lead from? The high empathy section could be too emotionally draining and potentially even messy by comparison.

Hey, Darren. I wrote a response on Thursday, but I must not have posted it. I think bootstraps is probably the easiest place to lead from in particular in positions with de facto authority. If I was a boss with people who worked for me and needed to keep a pay check then leading without compassion would be the easiest emotionally in the short term. I’m not sure of how long that works in non-profits or churches where my volunteers could leave.

Thanks for your nuanced and biblically sound analysis, Robert.

I’ve noticed a rise in the use of terminology like “empathy deficit disorder,” “hyper empathy,” and “toxic empathy.” Something tells me that we struggle to get the balance right.

Ultimately, I don’t think it’s a binary case of “yes” or “no” to empathy, but ensuring that we avoid unhealthy behaviors like, as you describe, a lack of compassion or, at the other end of the spectrum, projecting the emotions of others for our own personal gain or fulfillment. I personally appreciated Friedman’s analysis but think there’s definitely more nuance to the concept. This seems to shine through in some parts of his writing like describing that we can afford to have empathy only if we have the emotional maturity to ensure a stable system. Christ is the epitome of this, and this topic only highlights my deep need of him to lead well.

Joff, thank you. I enjoyed writing this week’s reflection. Like you, I tend to agree with Friedman’s analysis. I think in this point he’s wrong in nuance. I don’t know enough to know if that’s a product of the book being 30 years old – Our world is different now than when he wrote.

Just off the top of my head, I think there’s something about American culture that has a strong distrust for otherness. When coupled with increasingly unembodied relationships, this distrust has decreased healthy empathy.

There’s a fantastic taco food truck in my town. One of my MAGA parishioners said, “She’s one of the good ones.” He is racist and has an immigrant boogey-man that he is fearful of, but at the same time, he likes Maria and her tacos and is kind to her. They know each other by name. His undercurrent of distrust of otherness doesn’t extend to his embodied relationship with Maria. He has empathy for her and wants her to succeed.