“My flag is not racist!”

In “The War Against the Past: Why the West Must Fight for Its History,”[1] Frank Furedi, Emeritus Professor of Sociology at the University of Kent, examines the contemporary movement to denigrate Western history and its cultural heritage. He contends that this trend, manifesting through actions like toppling statues, decolonising curricula, and altering language, seeks to portray the past as a source of shame, thereby undermining societal identity and cohesion.

Summary of your most deeply held convictions before the readings and why I held/hold those beliefs

I have always been passionate about history. From the foundational developments of ancient civilizations which shaped our Judeo-Christian values, to the rich narrative of church history, I find immense value in exploring these stories. The art of storytelling and the opportunity to apply practical lessons from the past have consistently captivated me and shaped my perspective on the present.

I have equally had a leaning towards military history, whether it be the Spartans, Romans, Crusades, British Empire or the World Wars. The often-quoted “History is written by the victors”[2] is probably true. Voltaire’s famed statement, “All the ancient histories, as one of our wits say, are just fables that have been agreed upon,”[3] contributes to the sceptical view of history. While historical accounts have an inevitable leaning towards one people group and ideology over another, there is still much to learn from it. Aldous Huxley summarises the renowned statement regarding learning from history when he said, “Men do not learn much from the lessons of history, and that is the most important of all the lessons of history.”[4]

History taught me that any attempt to eradicate history is to not only question the identity of a people, but that if history can be erased, the future can be questioned. Whether it be the attempts by Hitler during the holocaust to erase Judaism’s future by destroying its past or, more recently, Isis’s destruction of archaeological sites or the tearing down of so-called racist statues as a convergence with the BLM movement, Year Zero Revisionism has caused me alarm for several years. The resurgence of presentism in our view of history once again proves King Solomon’s wisdom when he wrote, “There is nothing new under the sun” (Eccl. 1:9) nearly 450 years before Christ.

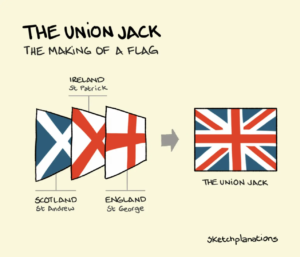

I feel a deep frustration toward those who label the British flag as racist. It has never made sense to me, either emotionally or intellectually. My response to those who criticise the Empire’s history is, “Show me a country whose sins have not included racism or slavery. (And no, they are not the same thing.)” Rebuttal against me will include the inevitable Identity Politicking around my gender, melanin levels, marital and academic status (yes, I tick off every box as the oppressor in CRT). However, the facts of history also reveal that Britain did more than any single nation to eradicate slavery. The use of her navy[5] over an extended period to seek and destroy slavery on the high seas is undisputed.

I was recently at a very senior function in some Government chambers in London. Throughout a series of meetings, I heard several speakers denigrate our flag as racist and that we, the British, should be ashamed of our past. Inwardly I was seething. Not that we should not lament the sins of our past, as all nations should, but the revisionist ideology was focused on destroying the good with the bad of our history. The meeting changed, however, when a very influential Nigerian-born, British-raised statesman stood to his feet in the hallowed halls and “thanked Britain for its role in eradicating slavery in Africa and bringing the Gospel to its shores.” It was a moment that took people’s breath away.

How have my beliefs been affirmed by the readings and were challenged and why.

I appreciated Furedi’s frankness and courage in writing what is sure to bring continued strong criticism from proponents of CRT[6] and all of its offshoot ideologies, of which I include Grievance Archaeology,[7] Year Zero,[8] and White Privilege[9] to name a few. Furedi’s chapter on the Gestation of the war[10] was helpful in revealing the events of how we got to where we are, whether it be the need to articulate trigger warnings[11] in museums or the teacher’s role in usurping parental wisdom. [12]

The author’s role in countering the popular revisionist tactics is helpful. Whether it be why decolonisation may not be overly helpful[13] or the arrogant assumption that we are more intelligent today than previous generations,[14] Furedi has successfully given a voice to those of us who acknowledge that, like every nation, we have shameful moments in our past but refuse to be labelled as racist or to accept the notion of a Year Zero.

Cultural Marxism’s influence on societal discourse has long rested on framing history as a struggle between oppressors and oppressed. Furedi’s argument that contemporary critiques of history disproportionately highlight injustices, such as colonialism and slavery, confirms this perspective. Activists and educators often elevate historical victimhood to a moral high ground, positioning Western civilisation as the perpetual oppressor. This practice, rooted in Marxist ideology, seeks to dismantle traditional power structures by reinterpreting history through a grievance-centric lens. Without holding back, Furedi writes, “For the advocates of moral anachronism, history serves as an instrument for narcissistic self-flattery.”[15]

In calling for a defence of the past, Furedi urges society to recognize and value its historical inheritance. He emphasises that while it is essential to acknowledge and learn from historical injustices, it is equally important to appreciate the positive accomplishments and ideals that have emerged over time. Furedi warns that a one-sided focus on the negative aspects of history can lead to nihilism and despair, depriving individuals of a sense of identity and continuity.

Summarily, Furedi’s The War Against the Past deepens the conversation around cultural Marxism and historical revisionism by affirming the perils of the victim-victor/intersectionality narrative while challenging assumptions about the role of critical judgment in historical interpretation. His critique calls for a balanced engagement with history that preserves identity and cultural heritage while remaining mindful of past injustices. By navigating these tensions, Furedi provides a framework for resisting reductive ideologies and fostering a richer, more constructive understanding of the past.

[1] Furedi, Frank. 2024. The War Against the Past: Why The West Must Fight For Its History. 1st edition. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

[2] Churchill, Winston. “History.” AZ Quotes. Accessed January 3, 2025. https://www.azquotes.com/author/2886-Winston_Churchill/tag/history.

[3] Voltaire. “Quote.” Quotes Guide. Accessed January 3, 2025. https://quotes.guide/voltaire/quote.

[4] Huxley, Aldous. “Quote Meanings and Interpretations.” Socratic Method. Accessed January 3, 2025. https://www.socratic-method.com/quote-meanings-and-interpretations/aldous-huxley.

[5] History Reclaimed. “The Royal Navy’s Campaign Against the Slave Trade.” Accessed January 3, 2025. https://historyreclaimed.co.uk/the-royal-navys-campaign-against-the-slave-trade/.

[6] Furedi, 95.

[7] Furedi, 4.

[8] Ibid, 62.

[9] Ibid, 141-142.

[10] Ibid, chapter 2.

[11] Ibid, 170.

[12] Ibid, 186.

[13] Ibid, 189.

[14] Ibid, 178.

[15] Ibid, 110.

10 responses to ““My flag is not racist!””

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Glyn,

I never knew that the British Flag was considered racist. Thank God for the gentleman that changed the tone of the meeting. Could anyone else, being of a different race or ethnicity have made that same statement in that meeting with the same results?

Within your denomination/churches have you seen of the ideologies that Furedi discusses seep in?

Hi Mate. In theory, anyone could have made the statement, but the impact would likely have varied depending on the speaker’s background. A Nigerian-born British statesman speaking in defence of Britain’s historical role in abolishing slavery carries a certain weight because it challenges the dominant narrative of Britain as solely an oppressor. His voice comes from a place of personal and national experience that disrupts the victim-oppressor framework.

If a white British leader had made the same statement, it might have been dismissed as defensive or revisionist. If a person from another formerly colonised nation had spoken, it would have depended on their specific national history and relationship with Britain. The reality is that lived experience and identity politics play a significant role in how historical perspectives are received today.

From a Christian perspective, the challenge is to ensure that truth is spoken in love (Eph. 4:15) and that we do not fall into the trap of favouring certain voices while dismissing others based on identity alone. A commitment to truth, humility, and reconciliation should shape how we engage in these discussions.

Glyn,

Always appreciate your perspective mate. How might you suggest that we as a culture, or a society, balance the cultural heritage while at the same time recognizing or acknowledging past injustices?

Hey buddy, a few things come to mind. Balancing cultural heritage with an honest reckoning of past injustices requires a biblical approach—one that values both truth and redemption. Several principles can guide us:

Acknowledge both the good and the bad – Scripture does not shy away from recording both the victories and failures of God’s people (e.g., David’s successes and his failures, Israel’s triumphs and its exiles). We should do the same with history, avoiding both revisionist shame and blind glorification.

Practice humility and gratitude – We should acknowledge that no nation or civilization has a perfect record. While recognising Britain’s historical failures, we can also celebrate the good (abolition of slavery, advancements in law, democracy, and the spread of Christianity).

Encourage redemptive narratives – we believe in God’s power to redeem broken things. Instead of erasing history, we should engage in redemptive storytelling, showing how societies can learn from mistakes, seek justice, and grow in righteousness.

Refuse ideological extremes – Whether it’s cultural Marxism on one end or uncritical nationalism on the other, we must avoid oversimplified narratives that see history only through oppression or only through progress.

Keep Jesus at the centre – Jesus calls us to be peacemakers and truth-bearers. The gospel should guide how we teach and discuss history, moving the conversation from blame to reconciliation.

Thanks for your perspective Glyn. How do you see the role of public discourse in shaping our understanding of history? What strategies can be employed to foster constructive conversations about historical events and their implications in today’s society?

Hi Debbie. Public discourse is crucial in shaping how history is understood and applied. However, much of today’s discourse is polarized, making it difficult to have honest conversations. Here are a few strategies to foster constructive dialogue:

Encourage Historical Literacy: Many arguments stem from misunderstanding or ignorance. Churches, schools, and communities should promote deeper engagement with history that includes multiple perspectives.

Model Civil Discourse: As believers, we can lead by example. James 1:19 reminds us to be “quick to listen, slow to speak, and slow to become angry.” Creating forums where people can express different views without hostility is vital.

Prioritise Storytelling Over Ideology: Instead of reducing history to ideological battles, we should focus on real stories of individuals, movements, and transformations that shaped the past. Personal stories disarm hostility and foster empathy.

Call Out False Narratives with Grace: Both historical revisionism and uncritical nationalism can distort the past. As Christians, we are called to stand for truth but to do so in a way that builds bridges rather than burns them.

Thanks for your post, Glyn. I really appreciate your love of history and your passion for the gospel. It brought a richness to this post.

Unfortunately, colonialism and the gospel are often coupled together. They are not the same thing, but often went out hand in hand. How might we decouple the gospel from colonialism to help our culture see the transformational power of Jesus and Christianity?

Great question mate. To decouple the gospel from colonialism, we must first acknowledge that while colonial expansion often carried missionaries, the message of Christ was never dependent on empire. Christianity is not a Western construct; it was born in the Middle East, spread organically to Africa and Asia, and continues to thrive worldwide, independent of any colonial influence. While it is true that some missionaries were entangled in the structures of empire, many genuinely sought to share the gospel out of love rather than conquest. The mistake of equating Christianity with European culture has led to misconceptions that the faith itself is an instrument of oppression rather than liberation. By emphasising the transformative power of Jesus, which transcends national and cultural boundaries, and by celebrating the way the gospel has been embraced in diverse cultural contexts throughout history, we can reclaim its true essence. The message of Christ is not about dominance but about reconciliation, redemption, and the restoration of all things, truths that stand apart from the failings of any human institution.

Graham, this is a great question, so I will tag on here. Glyn, thanks for your great response. From my experience in Africa, Gospel-sharing efforts that have been coupled with colonialism look very similar, even today. As someone who has traveled extensively, what have you seen to be effective ways of sharing the Gospel’s transformative story in culturally contextualized ways?

Hi Kari. I remember hearing many years ago about when the missionaries first moved to Papa New Guinea to share the gospel. The missionaries at that time had a tried and trusted way of sharing the gospel story, beginning with creation and building to the climax, where Jesus Christ, the Lamb of God, was slain for the sins of humankind. On the day in question, when they were due to deliver about the Lamb of God, the indigenous people of Papua New Guinea did not respond in the way that other nations had previously responded. The missionaries discussed it and realised that where other nations understood the importance of the Lamb, in local culture in Papa New Guinea, it meant nothing. The missionaries then retold the story and portrayed Jesus as the “pig of God.” This, of course, would be highly offensive in the Jewish culture, but in Papa New Guinea, the pig was the most precious animal in the local community. Portraying Jesus in this way caused the local people to understand the power of what Jesus accomplished, and many turned to faith because of it.