Leading from Within: Lessons from Friedman, Walker, Greenleaf, and Koch

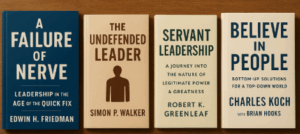

With so much attention paid to leadership frameworks and strategies, it’s easy to forget that leadership is ultimately not about tools or techniques, it’s about personal growth – who you are becoming. While I have studied leadership for many years, this post will revisit four leaders who have shaped my understanding of this truth: Edwin Friedman, Simon Walker, Robert Greenleaf, and Charles Koch, for whom I currently work through the Stand Together Foundation. In their own unique ways, each of these men insists that authentic leadership begins with presence and listening, confidence in one’s identity, and alignment with an inner moral compass that desires fairness and the good of all. Whether it’s Friedman’s idea of self-differentiation, Walker’s undefended leadership, Greenleaf’s servant-leader, or Koch’s Principle-Based Management™ (PBM), the message remains the same: to lead others well, you must first lead yourself, which in turn will help you earn the trust of others.

Friedman Revisited: Self-Differentiation in Anxious Systems

Until today, I have not visited Friedman’s “A Failure of Nerve” since it was introduced in a previous semester. What caught my attention was the reminder that, despite navigating through potentially challenging circumstances, we have agency to choose how we respond. Ah, yes, we can either absorb and further emit anxiety to others, or we can operate with a sense of calm and a straightforward demeanor, known as self-differentiation.[1] Navigating everyday pressures with this type of response conveys a sense of control and ease. A leader who appears confident and unrattled earns the trust of their followers much faster.

However, a particular nuance is at play for persons employed as fundraisers in nonprofit organizations. Fundraisers utilize a blend of art and science to lead with empathy and emotion, as emotional connection motivates people to take action.[2] The more urgency and feeling that can be communicated, the more compelling the need appears, and the more likely donors are to respond. In this model, emotion becomes both the tool and the currency of our work.

A consequence of having this type of job is that fundraisers are nearly always “on,” pitching, storytelling, and connecting; it’s easy to slip into the habit of seeing the world through an emotional lens before a rational one. Without realizing it, everything gets processed through urgency, empathy, and relational dynamics.

Friedman’s insight resonates with a personal truth. Anxious systems thrive on emotional reactivity, and leaders who are fused with the system can’t bring transformation. He challenges us to resist the pull of emotional fusion, not by becoming cold, but by becoming clear. I would argue that for those who are trained to draw out emotion in themselves and others, the ability to separate the two comes only with intention.

Walker Revisited: Leading from the Undefended Self

Where Friedman calls for boundaries, Simon Walker calls for openness. In The Undefended Leader, the author challenges leadership from the “undefended self” or a posture of vulnerability and presence, focusing on others. He argues that while many leaders have a frontstage appearance of confidence, they are actually leading from a backstage fear rooted in ego or self-preservation.[3] His insight into how egos are structured helped me recognize how often performance masks insecurity, and how damaging that can be.

Walker urges his readers to lead honestly rather than from a place of proving our worth. While this is a wonderful theory, natural bruises and other emotional wounds can impede its effectiveness. In my own case, family trauma has affected me at such a deep level that I will likely always have to battle the inner voice of negativity. I recognized this during a recent visit to a prison, where I shared part of my personal story. It wasn’t a strategic communications move, but rather an act of presence when the a-ha moment struck. How can I encourage young women who will follow me to lead with confidence in their self-worth when I struggle to do the same? Does admitting that make me a bad leader? No, it makes me an honest one. In Walker’s terms, this realization was a moment of softening the defenses. To me, it felt like obedience.

Leadership is a moral and spiritual journey. It is not about domination or perfection, but about becoming whole, including the bruised parts. For Walker, the true self leads not from control, but from love.

Greenleaf’s Servant Leadership: Power as Service

I have always admired Robert Greenleaf’s work on servant leadership. It adds a whole other dimension to the question, “Do those served grow as persons?” Studying Greenleaf’s work has helped me define my ability to recognize and call out leadership moments, especially those that may not initially appear to be leadership. Because after all, reading between the lines or what is not said in a conversation is a significant part of leadership, too.

For Greenleaf, leadership is found in service. When a task is performed with intentional presence and care, it becomes deeply dignifying for both the person being served and the one serving. Volunteering in prison, I hear the echo of Greenleaf’s insight through that still small voice: “This is what it means to wash the feet of Jesus.”[4]

Greenleaf and Walker share similar views on power. They feel it is not something to accumulate, but something to honor and steward on behalf of others. Both see vulnerability not as weakness, but as a doorway to transformation.

Koch’s Principle-Based Management: A Framework for Flourishing

Where Friedman, Walker, and Greenleaf offer inner transformation and posture, Charles Koch provides a principled framework for putting it into practice, particularly within organizations. Principle-Based Management™ (PBM) grounds leadership in the Principles of Human Progress, emphasizing dignity, mutual benefit, openness, and self-actualization.[5] The term management is a misnomer. Traditionally, management has been hierarchical; however, Koch firmly believes in a bottom-up empowerment model that must first come from within leadership.

Charles Koch grew up as the son of a farmer with a natural gift for innovation. He milked cows and plowed the soil from the age of six. This work ethic carried over into the family business, which he took over as his father’s health was failing. Smart as a whip, Koch learned through testing new ideas and comparative advantage. However, he also recognized threads of human empowerment, which he referred to as principle-based marketing, that undergird his entire private enterprise and his significant philanthropic work. In this realm, PBM is how we engage communities of concentrated potential. We collaborate with local residents to remove barriers and establish systems that foster human flourishing.

PBM’s Five Dimensions offer a blueprint for culture-building:

- Vision – Leading from a clear and principled purpose.

- Virtue & Talents – Ensuring the right people are in the right roles, guided by integrity.

- Knowledge Processes – Encouraging Bottom-Up Feedback and Discovery.

- Decision Rights – Giving decision-making power to those with the best knowledge.

- Incentives – Aligning rewards with long-term value creation.

This system aligns with what Walker, Friedman, and Greenleaf believe: leadership is not about status or control. It’s about aligning your inner life with your outer actions to empower others to thrive.

Where Walker gives language to the inner journey and Friedman to emotional clarity, Koch provides the framework for building principled organizations. PBM takes the soul of servant leadership and the clarity of self-differentiation and turns it into an operating system.[6]

Threshold Concepts: Identity, Power, and Presence

Across all four thinkers, a few threshold concepts emerge. First: Leadership is about congruence, not performance. In spaces where ego is rewarded and image matters, I’ve learned that inner clarity is more sustainable than charisma.

Second: Power isn’t about control. It is about presence. Whether it’s Walker’s undefended self, Greenleaf’s servant, or Koch’s view of principled empowerment, the throughline demonstrates that power rooted in fear leads to defensiveness and manipulation. However, power rooted in love leads to liberation and transformation.

Third: We absolutely must pause, think, and choose how we want to show up in anxious systems. As Friedman says, we can’t control the anxiety of a system, but we can control whether we absorb it. Remaining calm, clear, and committed to principle is a spiritual and strategic act.

Conclusion

Leadership in today’s world demands more than strategies and slogans. It calls for inner alignment, principled action, and the courage to lead authentically from within. Friedman, Walker, Greenleaf, and Koch offer different lenses, but together they create a rich and coherent vision of leadership that celebrates clarity, service, vulnerability, and integrity. Whether you’re leading in a nonprofit, business, or community, don’t just lead for impact. Lead for transformation, which doesn’t come from our outer influence, but rather can only begin at the center of our being.

[1] Friedman, Edwin H., Margaret M. Treadwell, and Edward W. Beal. A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix. 10th anniversary revised edition. New York: Church Publishing, 2017. P. 97.

[2] Ibid. P. 55.

[3] Walker, Simon P. The Undefended Leader. Carlisle: Piquant, 2010.

[4] Greenleaf, Robert K., Stephen R. Covey, and Peter M. Senge. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness. Edited by Larry C. Spears. 25th anniversary edition. New York Mahwah, N.J: Paulist Press, 2002.

[5] Koch, Charles G., and Brian Hooks. Believe in People: Bottom-up Solutions for a Top-down World. First edition. New York: St Martin’s Press, 2020.

[6] Koch, Charles G. Good Profit: How Creating Value for Others Built One of the World’s Most Successful Companies. New York: Crown/Archetype, 2015.

7 responses to “Leading from Within: Lessons from Friedman, Walker, Greenleaf, and Koch”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thanks Jennifer. I especially like, “Does admitting that make me a bad leader? No, it makes me an honest one.” How do you manage the tension between honesty/vulnerability and oversharing/turning the story on yourself in these settings. As a leader, I think this is a tension to manage; when to connect my own story and vulnerability and when to listen and communicate empathy and remain other-focused.

Thank you, Ryan. I agree with you, that being an authentic leader is difficult sometimes. The audience is always changing, so there isn’t a one size fits all answer.

Personally speaking, The blog I wrote last week disclosed more parts of my testimony than I have ever written. Most people know very little of my story or perhaps just one or two pieces. It was a pretty steady battle with myself to not go back and revise. I felt very exposed.

However, there was a freeing element in releasing what has been hidden for a long time. The discernment of when to share, what to share, and how much, will come as I see opportunities to help somebody with my testimony. Then I can use it to focus on other people.

Jennifer,

Your comment “In my own case, family trauma has affected me at such a deep level that I will likely always have to battle the inner voice of negativity,” along with last week’s book and our Zoom meeting reminded me of a local counselor, Terry Wardle, who taught at Ashland Theological Seminary and created the concept of Formational Prayer. I’ve heard him speak, read one of his books, and have several friends who studied under him.

https://www.healingcare.org/about

Question – Similar to what I asked Graham, if you had to choose one of the four books you discussed to give to someone in leadership which would it be and why?

Thank you for the link, Jeff. I saved it to take a look later this afternoon once I get off the plane back in Oklahoma.

To answer your question, I think there are two books I would offer. One is Simon Walker’s book and the other would be the Charles Koch book.

The reason is because Walker focuses on naming and understanding the qualities within ourselves, while Koch offers guiding principles on how to build leadership and empowerment in others (as well as ourselves). I have worked for a Charles Koch philanthropy since March, and I have to say, my entire way of thinking has shifted in terms of how I help others. It’s a positive move which actually builds on Dr. Fikkert’s book When Helping Hurts. Together, they present a very different yet complete package of how We serve people to help them reach their God-given potential, which is where dignity lives.

Jennifer,

I loved this, “it’s easy to slip into the habit of seeing the world through an emotional lens before a rational one.” How might we not neglect the emotional lens but understand the rational one at the same time. Our emotions are powerful and needed and we should respond to our emotions but it can be tricky. How have you navigated this?

Thanks Adam. I am still learning how to navigate this. I have been very well trained through decades of fundraising leadership that emotional pull is the call to action. Plus I’m hardwired to think that way. But what I can say is my husband is completely opposite in almost everything, which helps bring balance to my thinking and his. I watch and learn how he navigates difficult situations and often strive to follow his lead. He’s very steady – one of a zillion things I love about him.

Hi Jennifer,

I love this statement, ‘Leadership is a moral and spiritual journey. It is not about domination or perfection, but about becoming whole, including the bruised parts.’

My question honors the spirit of your statement. In these 3-years period I have known you, I’m amazed how involved you are in your community. How does leading from wholeness, rather than perfection, change the culture of the community you serve?