Imagine All the People…

There is a fun game that we play when friends come over sometimes called “Imagine If…” This game allows each player to link a real person (known to all the players around the board) to something that best describes that person. For example: “Imagine if Bill were a type of music. Would he be classical, hip-hop, punk rock, bluegrass, or country?” The game can bring a lot of laughs, but once in a while, someone’s feelings can get hurt, even though it is all in fun.

Charles Taylor’s book, Modern Social Imaginaries[1], asks serious questions about society and culture. “Imagine if society were yours to shape, what would it look like? Would it be a religious theocracy, Marxist/Socialist, capitalistic, a secular state, or pure anarchy?” Taylor postulates in his text that Modernity looks a lot different from antiquity for many reasons, some political, some religious, and some secular. He is a remarkable writer, philosopher, and theologian. To get a better understanding of Taylor, I looked online and found a very helpful clip on You Tube. The clip is called, “The Future of Religion” and features an interview with Professor Taylor and Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. The interview helped to give me a better perspective on Taylor’s views. Here is the link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RV2fDNVb1sc.

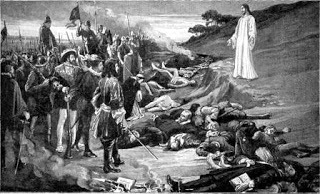

One of the theorists that Taylor credits for the state of modern (Western) society is Hugo Grotius, the Dutch philosopher/jurist. Grotius experienced firsthand the brutal religious wars of Post-Reformation Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and was appalled at what he saw. Grotius saw (imagined) a different world than the one he had experienced and entered the conversation of Just War Theory in a radical, unorthodox way. Eventually, Hugo Grotius became known as the “Father of International Law.”[2] His most important work is “The Law of War and Peace,” which he wrote after escaping prison and ending up in France. According to Paul Christopher:

The Central Theme of The Law of War and Peace is that the relations between states should always be governed by laws and moral principles just as relations are between individuals. This assertion is pivotal because, if true, it restricts both the authority of the Church and that of sovereign states (and their rulers). Such limitations on secular and Church authority are necessary if international laws are to have any force. But in order for his argument to persuade, Grotius must first show that just as there are moral principles operating in interpersonal relations there are analogous moral principles that are at the foundation of municipal (civil) laws. Only then can he stand any chance of convincing us that analogous rules apply (or should apply) in the society of states.[3]

Christopher continues to explain that what Grotius grounds his municipal law in is in a “law of nature.”[4] Grotius puts it thus, “[The laws are] unchangeable – even in the sense that it cannot be changed by God.”[5] This was indeed a new social order, and why not a new order? Grotius experienced the unbelievable carnage of Europe’s religious wars in which whole towns were annihilated. He declares in his own words that the reason he “imagined” The Law of War and Peace:

I had many and weighty reasons for undertaking to write upon this subject. Throughout the Christian world I observed a lack of restraint in relation to war such as even barbarous races should be ashamed of; I observed that men rush to arms for slight causes, or for no cause at all, and that when arms have been taken up, there is no longer any respect for law, divine or human; it is as if, in accordance with a general decree, frenzy had openly let loose for the committing of all crimes.[6]

In the years that I taught a course called War and Peace, Grotius became one of my heroes. Yes, he was a spokesman for secularity and humanism, but what is wrong with that? When the Church has become impotent in her calling, sometimes a different order must come into play. Grotius was not a villain; he was a man who was committed to doing what was right and just, and he was a person who stood up for reason and Christ-like values. Yes, we live is a different world now than in Grotius’ day, but we need to realize that sometimes God will use any means to bring us to a place of peace. For me, I will take a Grotius over brutality and butchery any day. So have Grotius and Locke’s Social Imaginary taken us too far? Perhaps. But if we need a new Western “Modern Social Imaginary” to change what it has become the past 300-400 years, I have an important question: Who has enough social imagination to stand up and make that needed change? Imagine all the people…

[1] Charles Taylor, Modern Social Imaginaries (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007)

[2] Paul Christopher, The Ethics of War and Peace: An Introduction to Legal and Moral Issues (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2004) 66-98

[3] Ibid., 67-68

[4] Ibid., 68

[5] Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace, translated by Francis W. Kelsey (Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1962) 40

[6] The Law of War and Peace, 20

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.