I have some context in my theology…..and so do you

As I was reading about contextual theology in our assigned works by Steven Garner and Stephen Bevans, I kept thinking about the ad campaign from Reese’s peanut butter cups.

As I was reading about contextual theology in our assigned works by Steven Garner and Stephen Bevans, I kept thinking about the ad campaign from Reese’s peanut butter cups.

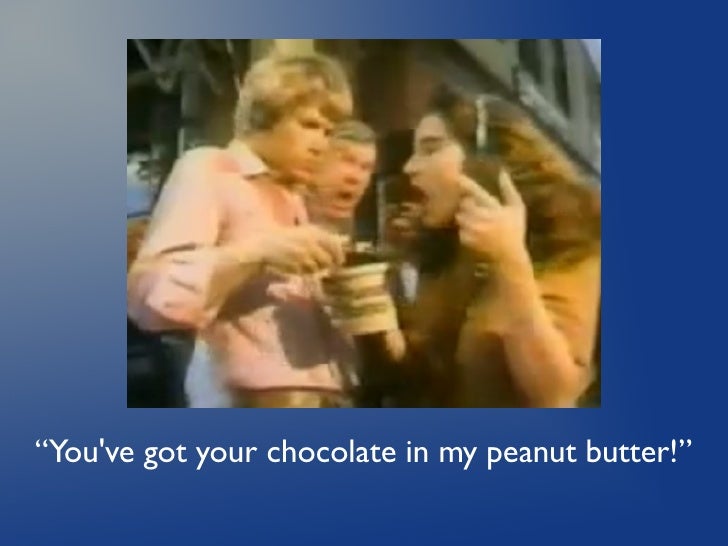

The ad (a picture from the commercial is on the left) was (in the most 80’s way possible) incredibly cheesy as it had two people, one carrying chocolate and one carrying a jar of peanut butter bump into each other and accidentally ‘mix’ their peanut butter and chocolate. They are initially furious until they learn what we already know, that peanut butter and chocolate is a delicious combination.

So, at times as I was reading these texts, Bevans larger overview of contextual theology, Models of Contextual Theology, and Garner’s short exploration of the values of contextual and public theology, Contextual and Public Theology: Passing Fads or Theological Imperatives?, I saw this commercial being played out with theology and our contexts playing the roles of chocolate and peanut butter.

In varying degrees of detail both Bevans and Garner highlight that in a very real way, all theology is contextual because all of our thoughts and actions come out of and are shaped, at least in part, but the context from which they arise.

As Bevans states (and Garner cites):

There is no such thing as “theology”; there is only contextual theology: feminist theology, black theology, liberation theology, Filipino theology, Asian-American theology, African theology, and so forth. Doing theology contextually is not an option, nor is it something that should only interest people from the Third World, missionaries who work there, or ethnic communities within dominant cultures. The contextualization of theology—the attempt to understand Christian faith in terms of a particular context—is really a theological imperative. As we have come to understand theology today, it is a process that is part of the very nature of theology itself. (Bevans, Kindle Location 188)

There are really two critical pieces of information to digest in that quote. First, that it isn’t only the theologies that arise from minority communities that need to be understood as contextualized. Black, liberation, feminist, theologies emerge because the dominant or majority theologies (which by virtue of their place of prominence and/or dominance don’t usually get a ethnic or contextual name) don’t adequately address their issues and contexts. When we ignore the truth that all theology is contextual we run the risk of confusing the structures of our current context with the structures of the gospel.

There is much more at stake here than accurate and precise theology at stake here. When we fail to recognize the influence that comes from our particular context, the result can be a corruption of the very meaning and nature of the gospel. An example of this is the many, many churches, pastors and theologians that supported slavery as the will of God – their theology of dominion of one culture (white/european) over another (black/african) was clearly influenced by their context. This is easy for us to see, because we are no longer in that context – but it serves as reminder to us of the importance of carefully examining our context and it’s influence on our thinking and theology.

I first made this connection in seminary as we were reading and discussing James Cone and black, liberation theology. The discussion was robust and many in the class reacted very strongly – some negatively, some positively – to Cone. Then someone asked this question: why do we need ‘black’ theology and shouldn’t all Christian theology be liberation theology by definition? This question led to the recognition that these theologies arose out of specific contexts to be sure, but also they arose in response to the inadequacies of the already existing theologies to speak to the context that so many were living in – because they were developed and arose out of a very different context.

The second critical piece of information is that this process of contextualizing our theology – or rather recognizing  that our theology is contextual is imperative. This imperative is tied up in the nature of the gospel and in our call to share it with the world.

that our theology is contextual is imperative. This imperative is tied up in the nature of the gospel and in our call to share it with the world.

I see this as being connected to the idea that Jesus talks about in Matthew 9, the ongoing process of ensuring that there are new wineskins for the new wine. And this is the challenge of discussing and parsing out what it means to be a faithful Christian and what faithful theology looks like in our or any context. We worship a God that exists as an historical figure (and hence in a particular context), but we believe that historical figure brought salvation and Good news that we believe is for all people – in all times and contexts.

So the question becomes what has to be preserved from Jesus’ historical context and what is just that ‘context’ that can and should be flexible or contextual and is best left behind with the old wineskin.

Context matters!

For me, I have found much value in the praxis model of contextual theology paired with a strong dose of public theology. Garner gives the ‘classical’ definition of public theology by quoting Duncan Forrester, ‘theology which seeks the welfare of the city before protecting the interests of the Church, or its proper liberty to preach the

Gospel and celebrate the sacraments’ (Garner, 25). This is, to my understanding, a fundamental understanding of what it means to be the church – we do not exist for ourselves, but rather to be God’s ‘hands and feet’, Christ’s body serving in the world.

And the Praxis model of contextual theology provides an appropriate way of doing that, namely that the Praxis model compels us to move from reflection towards action. Asking of our faith and theology, in essence, ‘so what?’ or ‘what difference does it make?’. The Praxis model is so compelling because it isn’t content to describe what we might think or believe about God, Jesus, our faith, etc. but it connects that belief to action that is consistent with it.

Like it or not, aware of it or not all of us have a lot of context in our theology – when we acknowledge that and wrestle with that context, it enriches our understanding and helps us to more clearly communicate the good news of the gospel within our particular context.

10 responses to “I have some context in my theology…..and so do you”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Good post Chip. To get to the “orthopraxis”, we have to start with “orthodoxy” don’t you think? What we think and believe, our doctrine and theology, is vital to our practice. Paul’s letters often start with the theology, the doctrine, the truths about God and Christ, and then get to the practice, the outworking of that truth in their workplaces, and marriage, and family life, and community. I still think there are “right” things, true things, objective things, that we have to believe if we are to contextualize our faith!

Geoff,

I completely agree! There are objectively true things – certainly about God and his relationship and interaction with us…. And I think, as you said, it is critical to be able to recognize those things and then appropriately contextualize them.

I do think – or at least suspect – that we have often (and maybe still?) confused elements of our context with objective truths. Is there a better example of that than some people’s insistence on using the King James Bible?

“Then someone asked this question: why do we need ‘black’ theology and shouldn’t all Christian theology be liberation theology by definition?” Chip, that’s a good question. I also thought that the authors made a good case for Christians to be countercultural. The chocolate gospel message, doctrine and theology gets into the gooey peanut butter, real life in its context. I loved your illustration. It also carries the discussion of the “rational” vs. “empirical” that Jason started last week. Somehow, it’s a both/and. But for me, the locomotive is the truths about God in the Scriptures.

Yes, Mary! And I love the image of the truths of God revealed in Scripture as the locomotive that moves and drives us….. but I do still struggle with how we can be sure we are cleaving to the truths and not the context

Good word, Chip. These readings have had me thinking a lot about Prosperity Theology (something that I am not a fan of).

It is actually fascinating that one form of prosperity theology is espoused by affluent, white men who justify their extravagant lifestyles as a sign of their superior faith and God’s superior blessings.

This theology has also been adopted by hundreds of thousands of Africans and Latinos around the world (including African Americans and Latino Americans).

For me, the idea of prosperity theology causes me to pause when looking at contextual theology.

For example, just because a conextualized “Polygamy Theology,” “Nudist Theology”

or “Marijuana Theology ” exists, does not mean that it is sound theology.

Stu – prosperity gospel, in my opinion is not the gospel! But you are right, that it does highlight what happens when we try to make the gospel fit around our context (or what we want to be our context to be) instead of the other way around..

And I would argue that when “heretical” theologies arise such as the ones you suggest (even the prosperity gospel), it is the work of the global hermeneutical community to challenge them, which in fact many people do re: prosperity gospel.

“The Praxis model is so compelling because it isn’t content to describe what we might think or believe about God, Jesus, our faith, etc. but it connects that belief to action that is consistent with it.”

Chip so true! A theological model that isn’t content but connects and is consistent in action is what is needed so desperately today. I like you have had the same discussion in Seminary about what contextual theology is even needed and practiced. I found it interesting that the reasons provided by others to defend their point of view came directly from their personal experience and cultural context. So ironic. I was amazed when I read a book on from a Latino theologian. First I connected to the similarities based on their cultural context but I was also drawn by our differences and why they see and understand God in that way. It was so refreshing and eye opening for me. As a Church we need more understanding of God that is witnessed by others whose theology is shaped by the 3 dimensions.

Chip awesome writeup

We all should use context in our theology. There are some I know take a verse and use it to preach and speak on. It can be done if it is used in the context of the scripture and properly applied to life application. There are those who do not use it in proper context and therefore people take it and misapply it in their life. We must consider our audience when presenting our text, to ensure that what we are saying reflect who they are and their lives.

“it isn’t only the theologies that arise from minority communities that need to be understood as contextualized. Black, liberation, feminist, theologies emerge because the dominant or majority theologies (which by virtue of their place of prominence and/or dominance don’t usually get a ethnic or contextual name) don’t adequately address their issues and contexts. When we ignore the truth that all theology is contextual we run the risk of confusing the structures of our current context with the structures of the gospel. When we fail to recognize the influence that comes from our particular context, the result can be a corruption of the very meaning and nature of the gospel.”

I want to give a loud “Amen!” to that. We cannot remove our context-colored glasses, but we can add other lenses to them, seeking out voices that stretch us from our comfort zone. And maybe those “named” theologies can provide a bit of the prophetic word that Geoff in his blog post aptly reminds us our dominant culture needs to hear.