Decision-Making and Uncertainty

The reading this week was Thinking, Fast and Slow by Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman.[1] I looked forward to this book above all other entries on the reading list. This one deserved more than inspection, and Kahneman did not disappoint.

I first came across Kahneman and his colleague, Amos Tversky, in a historical review of risk-taking by Peter Bernstein.[2] He credited Kahneman and Tversky as conducting “the most influential research into how people manage risk and uncertainty.” My readings typically involve equations, so books like Ang and Tang have been the norm.[3] Kahneman wrote on familiar risk and decision-making topics, but his focus was on the why behind the what that I have studied.

Many of the illustrations involved simple gambles, reflecting that “every significant choice we make in life comes with some uncertainty.”[4] This is my language: expected returns, small sample sizes, and bias. If I am the random sample representing our cohort, then everyone fired up Excel to compute the Bayesian probability that the cab involved in the accident was blue.[5] Such a conclusion would be a planning fallacy as well as a mischaracterization of how normal I am.

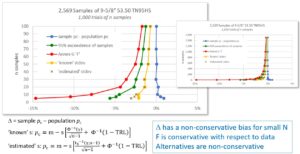

Figure 1 – An Expensive Plot of Bias with Small Sample Size

The read was time consuming. Kahneman would describe his observations, and I would pause to survey my hard drive for instances that came to mind. One of the more compelling correlations between his theory and my experience was his description of interviewing military recruits to determine fitness for combat. Kahneman observed that clinical interviews failed because they “allowed the interviewers to do what they found most interesting.”[6] Forty minutes later, I had successfully dug out my 2009 Leadership Development Assessment to have a chuckle. I could not have cared less about the LDA, a necessary step for getting a managerial salary for my specialist job. The psychologist picked up on my obvious signals and dismissed my potential because I needed to improve my interpersonal impact when meeting an unfamiliar person. Kahneman nailed it. My assessment was about the interviewer, not the interviewee!

Application to Leadership

All of this is fun, at least for me. How does Thinking, Fast and Slow relate to leadership? The work highlights that our brains are powerful and imperfect. To improve decision-making, Kahneman observes that organizations naturally think slower than individuals—a tactic of invoking System 2—and can enforce processes and procedures which address pitfalls like optimism bias or WYSIATI.[7] Two examples come to mind.

The first involved a multi-year study on high profile, catastrophic industry failures. Through research and interviews, I cataloged and grouped a wide variety of equipment and metallurgical failures. The stated goal for Lessons Learnt, Vol. I was to identify the underlying causes, which would then underpin Vol. II, which would provide a strategy for preventing future failures. Kahneman put names to this misguided System 1 way of thinking, like belief in the law of small numbers and hindsight bias.[8] Thankfully, System 2 was engaged prior to launching Vol. II. The biggest lesson is that we don’t know what we don’t know—the same concept that Donald Rumsfeld later called “unknown unknowns.”[9] Rather than foolishly claim an end to future failures, Vol. II was replaced with a recommendation for how to build an organization oriented toward responding to incidents and transferring knowledge.

The second example of improving organizational decision-making came from a study on competitiveness. My department had overreacted to a previous incident by requiring every engineering document to undergo cross-discipline reviews. It was common to have twelve signatures on a 160-page report, effectively guaranteeing that no one individual was responsible for the comprehensive plan. This was akin to the study of students who did not aid a choking person because someone else could help.[10] Improvements included clear accountability assigned to one engineer and their direct supervisor (two signatures), conducting training on fallacies like continuation bias, and adding a designated challenger role to risk assessments such that System 1 decisions were openly questioned by a System 2 thinker (we do not use Kahneman’s language, though). We still have room to travel for dissemination of learnings.

Kahneman has shared how people think and how decisions are made. His conclusion related to organizational procedures is a counterpoint to Friedman’s teaching that leadership is emotional.[11] I would suggest that the values and behaviors of the differentiated leader are emotional but should be underpinned with a cognitive understanding of how organizations work. Both works contribute.

[1] Daniel Kahneman. Thinking, Fast and Slow. 1st pbk. ed. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013).

[2] Peter L. Bernstein. Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1996), 270.

[3] Alfredo H.S. Ang and Wilson H. Tang. Probability Concepts in Engineering Planning and Design, vol. I, Basic Principles. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1975).

[4] Kahneman, 270.

[5] Kahneman, 166-67.

[6] Kahneman, 230.

[7] Kahneman, 418.

[8] Kahneman, 113, 202

[9] Donald Rumsfeld. “Known and Unknown: Author’s Note.” The Rumsfeld Papers, Accessed March 5, 2025. https://papers.rumsfeld.com/about/page/authors-note.

[10] Kahneman, 170-71.

[11] Edwin H. Friedman. A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix, ed. Margaret M. Treadwell and Edward W. Beal, rev. ed. (New York: Church Publishing, 2017), 14.

6 responses to “Decision-Making and Uncertainty”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rich – Thanks for your post!

It’s always enjoyable for me to read through how you process our readings–I (mostly) jokinlgy tell people I went to Bible school because there wouldn’t be as much math there. I appreciate your perspective and insights.

I found congruency between Friedman and Kahneman, especially as it relates to being present as leaders: we bring all of who we are–cognitively, emotionally, spiritually, physically–into the work of leading others toward a preferred future. Kahneman really challenged me in the “cognitively” space. What insights do you have on bringing that full presence when we might have stengths or proclivities more in one arena than the others?

Thanks for the prompt, Jeremiah. I will bring Poole’s 17 Critical Incidents into the mix.[1] This exhaustive list falls under the chapter title, “What Do Leaders Need to be Able to Do?” It could be demoralizing for a leader to look at that list, fixate on the items of relative weakness, and conclude they are not fit for leadership. Why get out of bed?

If you will permit, I will think out loud rather than write my syntopical essay and get back to you.

– Friedman calls for strong leadership in the face of anxiety

– Kahneman gives insight into how we think and how decisions get made

– Poole details what is needed to lead and a bit on how to get there

Expecting you as a pastor to do all of the above is an exhausting and ultimately impossible task. Ah, but we do not lead in a vacuum. Poole includes delegating and listening. Kahneman calls for an organizational approach to think slow.

We do not need–nor will we find–a do-everything leader. Rather, a diverse leadership team allows individuals to contribute from their strengths while covering the range of organizational needs.

[1] Eve Poole, ‘Leadersmithing: Revealing the Trade Secrets of Leadership’. (London: Bloomsbury Business, 2017), 10-32.

Thank you, Rich!

Your response reminds me of the axiom that we don’t need to be “well rounded” leaders–we have strengths that we shoudl leverage… but we do need to have “well rounded teams” where everyone’s strengths are brought to the table and we all benefit. I think as a senior leader, we are responsible to hold the space where that can happen.

Thanks again!

Your second example on organizational decision making does show a senseless overreaction to past mistakes. Requiring twelve signatures spread accountability so thin that no one really owned the decisions—kind of like the bystander effect.

Giving clear responsibility to just two people was a great improvement. Adding, what I see as a “devil’s advocate” role for risk assessments seems inghenioues. They help ensure smarter, more accountable decisions. It’s a great start to making decision-making smoother and more effective. A good checks and balance is to have system two do the higher cognitive processing of the system one’s reaction.

Devil’s advocate is a good title. If the role is not clearly identified, then ‘jerk’ or ‘idiot’ can be mistakenly used.

As I continue to reflect on the last few books, it would be harsh to label the twelve signatures as a failure of nerve. Nevertheless, the anxiety of an organization that felt it could not survive another major incident led to many decisions that were ultimately unwound. We became very slow with decision-making, something that both Poole and Friedman wrote about. Kahneman tells us to slow down to invoke System 2, yet Poole describes a continuum bounded by ‘Shoot from the Hip’ and ‘Analysis Paralysis’.[1] If leadership was easy, then everyone would do it.

[1] Eve Poole, ‘Leadersmithing: Revealing the Trade Secrets of Leadership. (London: Bloomsbury Business, 2017), 15.

Hi there, Rich, I enjoyed your post, especially the part of your post discussing the working of implementing system 2. It was impressive to have so many signatures required for the 120 page document. Isn’t it wonderful to have language for the systems your team created and/or is doing? You have such a thorough understanding of this book. How would you train your team and others for a simple knowledge of this system in the future? I’d be interested in hearing your working knowledge for future teams on other projects.