Arthashastra

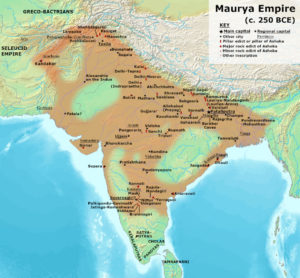

Have you ever heard of Arthashastra? I hadn’t until this week’s assignment. Led by my curiosity about what 300+ year old books on leadership might exist in Asia, I was delighted to find an ancient book from the sub-continent of India that predates much of what is considered classical treatises on leadership and statecraft from European and western perspectives. Arthashastra was written more than 2000 years ago, around 300 BCE.[1] Along with author, Kautilya, it was particularly influential during the time of the Mauryan Empire and its expansion.

Discovery and Significance

Arthashastra was discovered by R. Shamasastry in 1905 CE who then published the work in 1909 and translated it into English in 1915. The treatise was considered lost after the 12th century. However, its existence was known through references to it. The Arthashastra is recognized as one of the most important works on statecraft.[2] This ancient work remains popular in India and a source of national pride. It’s studied in universities and valued for its practical application in the modern world.

Arthashastra is frequently compared to Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince, published in 1532. However, Kautilya’s treatise is much more comprehensive. His instructions on war, dealing with enemies, and espionage are particularly troubling and specific. Beyond its age another striking difference is the book’s length. The English translation is 494 pages long! By contrast, The Prince is 99 pages. The Arthashastra is a meticulous guide describing in great detail how a king should rule his kingdom, with the chief aim to instruct the king in practical matters.[3]

Authorship

Arthashastra is attributed to Kautilya, also known as Chanakya and Vishnagupta. Kautilya was born into a Brahmin family sometime during the Nanda dynasty during the 4th Century BCE. He was a philosopher, political strategist, and royal advisor. According to legend, he was humiliated in the courts of King Dhanananda the ruler of Magadha and sought revenge. Under Kautilya’s counsel, Chandragupta Maurya destroyed the Nanda dynasty, became ruler of the Magadha kingdom, and founder of the Mauryan Empire which united the Indian sub-continent. Kautilya became advisor to Chandragupta and his son Bindusara, the second emperor of the Mauryan Empire and father of Ashoka the Great.[4]

Authorship is debated in terms of the three names associated with Kautilya. Many scholars validate the claim that they are one and the same person, while others consider three separate authors plausible.[5] It is thought that others contributed to composing, expanding, and redacting the treatise between the 2nd century BCE and 3rd century CE.[6] Kautilya remains a popular and enduring figure in Indian academia and culture as exhibited through continued interest, plays, and popular television series about his life.[7]

In Sanskrit the words Artha means “aim” or “goal” and Shastra “treatise” or “book.” The goal of the treatise is a comprehensive understanding of statecraft which enables a monarch to rule effectively, primarily through the flourishing of material well-being.[8] Common translations of the title are The Science of Politics, The Science of Political Economy, and The Science of Material Gain.[9] Arthashastra is divided into 15 books covering topics such as: discipline and character, the duties of government superintendents, law, justice, conduct of courtiers, invasion, war, and the work of spies.

Kautilya Says…

Regarding the virtue of the king:

“The king who is well educated and disciplined in the sciences, devoted to good Government of his subjects, and bent on doing good to all people will enjoy the earth unopposed.”[10]

“Restraint of the organs of sense, on which success in study and discipline depends can be enforced by abandoning lust, anger, greed, vanity, haughtiness, and overjoy.”[11]

Insights into governance:

“Sovereignty is only possible with assistance.”[12]

Qualifications of ministerial officers:

Native born of a high and influential family, wise, intelligent, eloquent, pure character, loyal, brave, skillful, free from procrastination, fickle-mindedness, and any qualities that excite enmity and hatred.[13]

Caste and Religious Influence

It’s important to note the theo-political perspective of Arthashastra. Kautilya references his Brahmin upbringing and the triple Vedas in which the four castes and four orders of religious life have influenced his ideas of statecraft.[14] The emphasis on character, discipline, education, and governance at the beginning of the book are a deep contrast with later chapters referencing the conquering of other lands for material gain and war time tactics.

Interpretations

Recent scholarship of Arthashastra continues to clarify the ideas of Kautilya. For example, Max Weber who appears to be the first political thinker to address the similarities between Kautilya and Machiavelli noted, “Truly radical “Machiavellianism”, in the popular sense of that word, is classically expressed in Indian literature in the Arthashastra of Kautilya (written long before the birth of Christ, ostensibly in the time of Chandragupta): compared to it, Machiavelli’s The Prince is harmless.”[15] Roger Boesche considers Kautilya to be the first great political realist.[16] He argues that Kautilya encouraged imperial expansion and had no qualms about advising for the conquering other kingdoms during times of economic stability and prosperity.[17] Stuart Gray broadens the lens in which to understand Kautilya. He suggests Kautilya is not a radical political realist but rather traditional, conservative political thinker and considers Arthashastra a work representing “brahmanical-Hindu political thought.”[18] Of modern day significance, Gray contends, “Kautilya’s political-theological realism furnishes a mirror for our own condition and helps us identify our potential blind spots.”[19]

With such a cursory read it’s hard to know what to think of Arthashastra. It’s an impressive and ancient work filled with virtue, yet boldly suggests that prosperous well-ruled nations have the right to invade and take what is not theirs by any means for the betterment of their people. I appreciate Stuart Gray’s idea that Arthashastra can serve modern-day readers as a mirror highlighting the absurdity of claiming a just form of rule while acting unjustly toward those with less power.

[1] Roger Boesche, The First Great Political Realist: Kautilya and His Arthashastra (Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, 2003), 2.

[2] Joshua J. Mark, “Arthashastra.” World History Encyclopedia. Last modified June 23, 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/Arthashastra/

[3] Stuart Gray, “Reexamining Kautilya and Machiavelli: Flexibility and the Problem of Legitimacy in Brahmanical and Secular Realism,” Sage Publications, Vol. 42(6) (2014), 638. DOI:10.1177/0090591713505094

[4] Kautilya. Arthashastra, First published 1915, translated by Shamasastry, (Fingerprint Classics!: New Delhi, India, Reprint 2023), Introduction.

[5] Joshua J. Mark, “Arthashastra.” World History Encyclopedia. Last modified June 23, 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/Arthashastra/

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthashastra

[7] Kautilya. Arthashastra, Introduction.

[8] Stuart Grey, “Reexamining Kautilya and Machiavelli, 638.

[9] Joshua J. Mark, “Arthashastra.” World History Encyclopedia.

[10] Kautilya. Arthashastra, 21.

[11] Ibid., 22.

[12] Ibid., 24.

[13] Ibid., 26.

[14] Ibid., 17.

[15] Max Weber, Politics as a Vocation (1919). This translation is from Weber: Selections in Translation, ed. W. G. Runciman, trans. Eric Matthews (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 220.

[16] Roger Boesche, “Moderate Machiavelli? Contrasting The Prince with the Arthashastra of Kautilya,” Critical Horizons 3, no. 2 (2002), 253-257.

[17] Roger Boesche, The First Great Political Realist: Kautilya and His Arthashastra (Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, 2003), 4.

[18] Stuart Grey, “Reexamining Kautilya and Machiavelli, 638.

[19] Ibid., 651.

12 responses to “Arthashastra”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I want to give you a prize or something for highlighting a book that I have certainly never heard of. I appreciated learning about it. I also resonate with your closing line regarding the hypocrisy so common when we look at those in power: “the absurdity of claiming a just form of rule while acting unjustly toward those with less power.” I wonder what modern day examples of similar hypocrisy come to mind?

Thanks, Kim! I think I wrote more of a book report than a syntopical review. It was fascinating. I can think of several examples with the current wars and among world leaders of our generation. In my Asian context Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge come to mind. But I also wonder about our own hearts no matter how big of a leadership influence we have derailers and wrong motives come in various sizes and circumstances that cloud our perception, discernment, and actions.

Yes, as I was reading your work, I thought: Not a lot has changed! Without divine intervention human nature will push all of us toward leading from a place of self-centered ambition rather than humble service… even if in the end it is absurdly self-defeating. Nice work on a difficult read!

Thanks Jennifer,

The ancient context was fascinatingly detailed and brutally honest. The contrast between a ruler truly wanting what’s best for the common good of his people, but then taking it to a level of detailed instructions for acquiring land belonging to others was troubling as well as incongruent. It starts our rather noble, but ends ignoble. Which does have me questioning Kautilya’s motives, but such is the nature of man, and the ability of power and wisdom to be corrupted.

Wow…good for you Jenny! I found your summary quite intellectually demanding…so I can’t imagine making my way through the entire book!

I found your one quote of Kautilya quite interesting:

“The king who is well educated and disciplined in the sciences, devoted to good Government of his subjects, and bent on doing good to all people will enjoy the earth unopposed.”

I read that as differentiating being able to rule through to power and, to some degree, threat to use that power against another…and being able to rule through influence and relationship, because people trust your intentions (to do good to all). I’m not sure if I am interpreting that correctly or not…but I am, I suspect that is a pretty radical thought at the time of writing.

Did he have other thoughts related to the relationship between a ruler (leader) and his subjects (followers)?

Thanks Scott, Full disclosure… I did not read the entire book, but I did read significant portions. Of the 15 books there are multiple chapters, which are thankfully short but often complex. In my opinion your interpretation is accurate. To answer your question about the relationship between ruler (leader) and subjects (followers), yes there are many references within the work. Many seem to be the expectations imposed on various members of society. Though the caste system was not legalized until much later. That system seems foundational in terms of Kautilya’s vision of society and governance running smoothly and maintaining order. There are many chapters detailing the roles for superintendents of various trades and government offices. Harsh punishments for superintendents and workers who fail to produce or act honorably are described (exile and cutting off thumbs are are just a few punishments that stand out). It feels very controlling, even if the underlying sentiment is for the common good. The idea of providing a stable way of life for one’s subjects through fear, control, and even benevolence gives an awful lot of power to one man, that can easily be corrupted. In the end, the Mauryan Empire ended with the assassination of its 9th emperor, Brihadratha, by his commander in chief in 185 BCE.

Thank you for the exciting book selection and description, Jenny! You write, “In Sanskrit the words Artha means “aim” or “goal” and Shastra “treatise” or “book.” The goal of the treatise is a comprehensive understanding of statecraft which enables a monarch to rule effectively, primarily through the flourishing of material well-being.”

This is some of the profound wisdom to be found in the Arthashastra.

In your opinion, which of these virtues aligns with the biblical values?

Hi Dinka, Thank you for your comment. I am not sure there is much that indicates biblical values beyond the types of quotes I used in my post. I may just be having a hard time with the harshness of the book. I think that is why it was so striking that the virtues of the ruler and his superintendants were so incongruent with behavior. Virtue, values, discipline, and character seemed very important to Kautilya, but it feels like a ploy to control, by gaining wealth and security, ostensibly for everyone. I wonder how virtuous Kautilya and the emperors he advised really were.

Dinka, I’ve been thinking more about your question and the book I chose. There is a tension between doing what’s right to create a society that prospers in which the people’s needs are met and the temptation of how far to go in securing a nation’s wealth. I think it’s personal too. How much is too much? Anytime the pursuit of more means taking away from others is too much, I’m reminded of what Jesus said in Matthew 6:24, “No one can serve two masters…. you can not serve both God and money.” God calls us to be generous and give out of what little or much we have, not to take that which does not belong to us, and then call it good, necessary, or right. Arthashastra starts as a benevolent concept that aims to bring order and wealth for the common good, but as wealth is acquired the need to protect it and the desire for advancement turns into conquest. What about concern for others(particularly outside one’s identity group) and generosity? Those virtues are not readily apparent in Kautilya’s thinking.

You ended with this summary quote: “I appreciate Stuart Gray’s idea that Arthashastra can serve modern-day readers as a mirror highlighting the absurdity of claiming a just form of rule while acting unjustly toward those with less power.”

Seems like with political rule, there really and truly is nothing new under the sun. How can we claim Justice and act unjustly toward those we lead! Thank you for tackling this book Jenny, impressive!

Jana, I seem to be hitting the wrong reply bottom a lot lately. I did respond to your post below.

Hi Jana,

My sentiments exactly…there is nothing new under the sun! It does raise the question of what is truly for the common good, and does that common good include everyone, just my nation, or people like me? I found the book to be ruthlessly honest in that it helps one see just how far off governments and human beings can get when seemingly trying to do what is right. I wonder how a similar book about the US (or any nation for that matter)would read if we were honest about our tactics and motives.