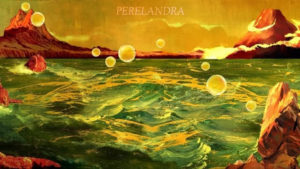

The Wounded Leader and the Waters of Healing

In C.S. Lewis’ Perelandra[1], when Ransom arrives in the distant Edenic world of Perelandra, he is not healthy. Instead, he arrives wounded, disoriented, and immersed in tumult. His “splashdown” into the vast, living ocean of that unfallen world is chaotic: waves toss him, exhaustion overwhelms him, and he must struggle toward the safety of a floating island. Only after that desperate swim does the healing process begin. Not through magic, but through presence, environment, and willing surrender to a world not shaped by his own striving.

In C.S. Lewis’ Perelandra[1], when Ransom arrives in the distant Edenic world of Perelandra, he is not healthy. Instead, he arrives wounded, disoriented, and immersed in tumult. His “splashdown” into the vast, living ocean of that unfallen world is chaotic: waves toss him, exhaustion overwhelms him, and he must struggle toward the safety of a floating island. Only after that desperate swim does the healing process begin. Not through magic, but through presence, environment, and willing surrender to a world not shaped by his own striving.

Lewis shows that the world of Perelandra itself is restorative. Its fruit nourishes, its waters cleanse, and its very air renews. Yet even there, Ransom’s healing is not immediate or complete. The “bubble-tree” shower that drenches him acts as a baptismal cleansing from the corruption of Thulcandra (Earth). The mountain pool that receives him after his brutal struggle with the Un-man offers rest and renewal. And yet his heel still bleeds. The wound remains as a sign of his encounter with evil, a reminder that healing is both real and incomplete on this side of glory.

Ransom’s experience is a parable of leadership in our world today. Leaders do not arrive whole. They arrive wounded by life, shaped by trauma, exhausted from storms they did not choose, splashing down into ministries and organizations hoping for stability and fruitfulness. But true healing requires more than competence or grit. It demands entering a different kind of environment, receiving cleansing and nourishment, confronting wounds honestly, and accepting that some wounds become teachers rather than vanishing marks.

This is precisely the world Nicholas and Sheila Wise Rowe describe in Healing Leadership Trauma.[2] Their work provides a critical lens for understanding why so many leaders today are not flourishing. They argue that leaders carry unresolved wounds that may include early life injuries, ministry harm, racialized experiences, gendered expectations, and chronic pressures that shape their inner world far more than they know.[3] These wounds produce patterns of self-reliance, self-protection, and relational isolation that are often mistaken for strength but are really just survival strategies.

This insight aligns deeply with my ongoing research. Many in my context are languishing, not because they lack talent or desire, but because they are convinced by a cultural map that has two primary navigational forces: social isolation and self-reliance. These forces are not neutral; they spring from the cultural myth of rugged individualism, akin to the myth of self-reliance that the Rowes reference.[4] These myths seduce many into believing that vulnerability is dangerous, wounds aren’t real, and therefore healing should happen privately, if at all. The Rowes show that such patterns are not merely cultural habits but often expressions of deeper, unaddressed wounds.

This dynamic is captured with striking clarity by Stanley Hauerwas, who observes,

We are afraid of showing weakness. We are afraid of not succeeding. Deep inside we are afraid of not being recognized. So we pretend we are the best. We hide behind power. We hide behind all sorts of things.[5]

Hauerwas gives theological language to the psychological realities the Rowes uncover. Our fear of being unseen, unsuccessful, or unworthy drives us to hide behind competence, influence, control, or ministry performance. Leaders do not merely drift into rugged individualism; we grasp it as a shield. We cling to power (or the appearance of it) because the alternative feels unbearably vulnerable. The Rowes reveal that beneath these defenses often lie wounds we have not named, let alone healed.

The Rowes seem to have embedded a five-part movement throughout their book, which serves as a pastoral and psychological map for stepping out from behind these shields. This process includes invitation, attachment, remembrance, healing, and reconnection. Leaders must be invited to name the truth of their wounds, revisit the attachment patterns that shaped them, remember painful stories without shame, pursue healing intentionally, and reconnect with God and others from a place of growing wholeness. This trajectory mirrors Ransom’s time on Perelandra: he arrives wounded, surrenders to an environment that can heal him, and emerges changed—but with a wound that reminds him of both his limits and his calling, not unlike Jacob walking with a limp after wrestling with God and receiving a blessing.

Considering the Healing Leadership Trauma alongside Simon Walker’s The Undefended Leader[6] and Andy Crouch’s Strong and Weak[7] clarifies why healing is so essential for leadership. Walker explains how wounded leaders behave. His distinction between the frontstage (public presence) and backstage (inner life) shows that many leaders labor to maintain a defended persona because they fear exposure. This defended stance is celebrated in rugged individualist culture but suffocates relational and spiritual life.

Crouch argues that flourishing emerges only when authority and vulnerability are both high.[8] Authority represents our capacity to act; vulnerability represents our exposure to meaningful risk. Rugged individualism champions authority without vulnerability; strength without weakness. But Crouch shows that such a posture results not in flourishing but in isolation, burnout, and exploitation.[9] Vulnerability is not the opposite of strength; it is the necessary companion to it.

Like Ransom on Perelandra, leaders need more than instruction; they need an environment where healing is truly possible. They need cleansing waters, nourishing fruit, and safe spaces where long-held wounds can finally be named. God has given these healing waters in the form of the local church. And, like Ransom’s bleeding heel, some wounds will remain, not as defects or disqualifications, but as reminders of God’s sustaining grace and the strength He provides.

__________________________________________________________________________

[1] C.S. Lewis, Perelandra, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1965).

[2] Nicholas Rowe and Sheila Wise Rowe, Healing Leadership Trauma: Finding Emotional Health and Helping Others Flourish, (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2024).

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] Ibid., 66.

[5] Stanley Hauerwas and Jean Vanier, Living Gently in a Violent World: The Prophetic Witness of Weakness, (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008), 64.

[6] Simon Walker, The Undefended Leader, (Carlisle, UK: Piquant Editions, 2010).

[7] Andy Crouch, Strong and Weak: Embracing a Life of Love, Risk and True Flourishing, (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2016).

[8] Ibid., 11.

[9] Ibid., 41–47.

17 responses to “The Wounded Leader and the Waters of Healing”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Chad,

Love your statement that “Leaders do not arrive whole.” I enjoyed your comparison to C. S. Lewis book. I started that trilogy once, a long time ago. Now I feel like I should actually read it. You mention a five-part movement in the book, invitation, attachment, remembrance, healing, and reconnection. Which one do you feel you struggle to step into the most?

Jeff, Thanks for the question. For me, the hardest step is actually the first one, invitation. Naming my own wounds and allowing myself to be drawn into the healing process doesn’t come naturally. I tend to default to self-reliance and “pressing on,” which can keep me from slowing down long enough to let God and others see what needs attention. Stepping into an invitation requires admitting I need help, which is exactly what rugged individualism trains us to resist. But I’m learning that healing begins when I stop trying to manage myself and allow God and trusted people to draw me in.

Hi Dr. Warren. Great syntopical work.

You have indicated that these self-reliant, self-protecting and isolationist tendencies are defence mechanisms. As my friend Brian says, “the shields are up.”

But since the process Rowe and Wise Rowe have laid out requires leaders, as you’ve shared, “to be invited to name the truth of their wounds,” what are your thoughts on keeping a leader from avoidance of what really needs understanding, self-compassion and healing?

Joel, That’s a great way to put it—“the shields are up.” I think the primary thing that keeps a leader from avoidance is a trusted invitation from people who are both safe and honest. In my experience, when leaders experience spaces of grace rather than judgment, they’re far more willing to lower their defenses and name the wounds that need attention.

Chad,

I am going to miss reading your posts. Maybe you can just continue to write them…

You write, “they need an environment where healing is truly possible.” If the leader in this case is a pastor who is leading a church, is it possible for the church to be the place of healing? Or would it be good for leaders to find a group outside of those whom they are shepherding?

Adam, I will commit to writing two more posts just for you. Thank you for a great question, and one I’ve wrestled with personally. I do believe the local church is meant to be a healing environment, but for a pastor to remain well-differentiated, it is different. A shepherd can be part of the flock, but there are limits to how vulnerable a pastor can be within the community they lead.

Because of that, I think pastors need both:

1) A church culture that practices grace, honesty, and relational safety, and

2) A trusted circle outside their congregation where they can be fully known without the dynamics of oversight or role expectations.

Chad! I love your analysis as you break down these readings. I can ask questions at a few junctures but when you spoke of vulnerability, we know from the pastoral perspective how many are burned in this area, and choose to stay isolated. What is the best way a leader can be vulnerable with those whom they have charge over?

Daren, that’s a real tension. It is very true that many pastors have been wounded because they were vulnerable. I think the key is what Andy Crouch calls “meaningful risk:” vulnerability that is purposeful, measured, and directed toward love rather than self-exposure for its own sake. Leaders can model this kind of wise vulnerability with those they shepherd, while entrusting their deepest wounds to a smaller circle of peers, mentors, or counselors who can hold that weight safely.

I resonate with this your thought, “But true healing requires more than competence or grit. It demands entering a different kind of environment, receiving cleansing and nourishment, confronting wounds honestly, and accepting that some wounds become teachers rather than vanishing marks.”

Thank you for sharing. I have a general question:

How does the book connect spiritual formation with healing from leadership trauma? What role does faith play in this process?

Shela, thanks for the question. The Rowes connect spiritual formation and healing by showing that true restoration happens in God’s presence and among God’s people. Their five-part movement isn’t just a psychological map; it’s a spiritual journey. Healing requires entering a different kind of environment, receiving cleansing and nourishment, and confronting wounds honestly. Faith is what makes that environment possible, and it’s what turns our wounds into teachers rather than vanishing marks.

Hi Chad, it’s so true that leaders arrive on the job wounded and shaped by trauma. Where do you see leaders in your own context experiencing “Perelandra-like” environments—spaces that invite healing rather than reinforce rugged individualism or self-reliance?

Christy, in my own context, I’ve actually seen a “Perelandra-like” environment emerging within our staff community at Easthaven over the last couple of years. As we’ve leaned into honesty, shared burdens, and deeper connection, the culture itself has become more like those cleansing waters where long-held wounds can be named without fear.

Beyond that, a couple of ministry debrief retreats in our valley offer short-term spaces for rest, reflection, and healing.

Chad, I read Lewis’s books SO long ago, I don’t remember a thing about them (I only read that series once, unlike Narnia, which I probably read 15 to 20 times). Thanks for the reminder about them. 🙂

I noticed that you kept your distance in this article. The author notes that Ransom’s heel still bled. So I’ll ask the personal question: what is one persistent wound or challenge from your own experience that you have learned to embrace as a “teacher” rather than hide as a weakness?

Debbie, I wasn’t intentionally keeping my distance in the article—I simply chose a more syntopical approach rather than a personal one. But if I name my own “bleeding heel,” it would be the absence of a father. I was essentially raised by a single mom, and that left me with lingering questions about legitimacy, worth, and what it means to be a man. That wound still surfaces at times, but instead of hiding it, I’m learning to receive it as a teacher. It has shaped the kind of father I aspire to be, and it continually turns my heart toward my heavenly Father, who has been faithful to shepherd me and the people I’m called to lead.

Chad, thanks for your post. Your NPO on rugged individualism probably intersects with mine. I’m looking forward to reading your work.

Great job bringing Lewis and Hauerwas into your post. You mention the local church as the “healing waters”, yet many leaders do not find this to be a safe place for healing. In fact, for many, it is the opposite. How can we support the local church in becoming a place of healing for pastoral leaders?

Graham, that’s an important question. When I describe the local church as “healing waters,” I’m naming God’s intention, not always our lived reality. The church can become a place of healing for pastors, but within limits. I explore this in more detail in my response to Adam’s question above.

Hi, Chad, thank you for the meaningful post. This is so common in our islanders’ communities as well as churches. The difficult part is that environment does not really exists to accommodate and to heal our Ransoms. If the church does not provide, and the community does not, what could be an alternative?