Miraculous Moments and Painful Processes

With Dr. Clark’s permission, I read Bring Me My Machine Gun (After Apartheid) by Alec Russell and Country of My Skull by Antjie Krog

When I read Bring Me My Machine Gun by Alec Russell and Country of My Skull by Antjie Krog, in preparation for the Cape Town Advance, I found myself not only studying the history of the country but also reflecting on my own story. I was born in South Africa a year after Nelson Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island. The island could be seen on a sunny day from the city and served as a reminder of what rebellion against apartheid could result in. Growing up in South Africa during apartheid meant that I didn’t encounter it as an abstract idea, but I knew it in the everyday rhythm and boundaries of life.

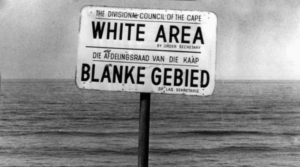

I grew up as a “Coloured” person, as labelled by the apartheid system, where people were identified by race. I remember the apartness that structured everything. It determined where you lived, which train you took, which school you could attend, which bathroom you could use, and which beach you could swim at. As a child, I accepted it, but I always felt the weight of a system that kept people apart and determined who was more privileged and less privileged.

In 1968, when I was just five years old, the apartheid government confiscated our family home on Hope Street in Claremont. Under the Group Areas Act, our neighbourhood was reclassified, and we were no longer “allowed” to live there. We were forced to move to a designated area for “Coloureds,” named Lansdowne. We were stripped of our rootedness and dignity. My uncle’s family were forced into a much worse situation, moved from a historic family home on the ocean in Simonstown into a ghetto-like town filled with drugs and gangs. Due to his colour, my father was demoted as the manager at his place of employment and made to train his supervisor.

My family moved to Canada when I was 11 years old, but it felt like South Africa never left me. This experience shaped and scarred me. It taught me early that identity in South Africa was something imposed on someone based on the colour of their skin.

I watched from Canada as Mandela was released from prison and then later elected as president in 1994. It seemed like an amazing miracle. I also heard from my family, however, that nothing had really changed for them, or for the country. I regularly hear from them about the poverty, unemployment, violence, unrest, and injustice that continue to plague the country. Just recently, in fact, I heard from them that they still feel stuck in the middle, between black and white.

The power of Machine Gun lies in showing how these structures of apartheid didn’t disappear overnight. Russel Writes:

The ANC made a steady start in tackling the legacy of white rule. It swiftly introduced a liberal constitution supported by independent courts that guaranteed rights long denied under apartheid. It revived the economy. It established South Africa as a presence on the world stage. But after fifteen years in power, the ANC is in danger of losing its way. It has catastrophically failed its two greatest challenges, AIDS and the collapse of Zimbabwe on its border. Now it is fighting to escape the shadow of so many other liberation movements that came to office with great dreams only to see them founder under the weight of unfulfillable expectations and against the backdrop of corruption, infighting, and misrule.[1]

Reading Machine Gun reminds me to hold two truths at once.

First, the miracle of political freedom. The peaceful transition in 1994 was improbable, even unthinkable. The fact that a nation built on such injustice could move toward democracy without descending into a civil war remains one of history’s great miracles.

Secondly, the slow, unfinished business of a nation’s transformation because of the scars remaining in the hearts of people. The system was dismantled, but the scars remain. Inequality, mistrust, and the enduring legacies of privilege and dispossession remind us that apartheid was not just a political system; it shaped souls. Transforming souls is a lengthy, gradual, and arduous process.

Years after settling in Canada, I met a white South African professional. He had grown up on the other side of the racial divide. His life was filled with privilege. And while my family fled to Canada to escape apartheid, he left to escape a post-Apartheid South Africa.

In one of our conversations, while on a walk, I told him that in 1968, my family home was confiscated by the apartheid government and that we were forcibly removed under the Group Areas Act. And it was taken from us without payment and without apology.

He was stunned. Not just by the cruelty of the act, but by the fact that he had never known it happened. “I had no idea,” he said quietly, shaking his head. “We were told nothing. I’m so sorry.” Having grown up in South Africa, he had never known the full extent of apartheid’s cruelty. In Country of My Skull Krog also noted that those who were listening to the stories of the victims of apartheid were realizing the full impact of system for the first time. That day, we walked for a long time in an awkward silence.

That moment was a moment of truth. Like most of us, he had grown up in a country that shielded him from the suffering of others. While it was a moment of truth, it didn’t change everything for us. Antjie Krog’s Country of My Skull recounts this reality. Her account of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was not just reporting an account she wrote as a white Afrikaner grappling with guilt, defensiveness, and with the language of her heart being the language of oppression. The book is hard-hitting and heartbreaking. The opening chapters are testimonies of the victims and the victimizers. Desmond Tutu, the architect of the TRC, is presented as highly optimistic, believing that once the truth is told, the country will be able to move on. However, this is not the case. Quoting a South African Psychologist in a later chapter, Krog writes:

“People thought that the Truth Commission would be this quick fix… and that we would go through the process and fling our arms around each other and be blood brothers forevermore. And that is nonsense—absolute nonsense. The TRC is where the reality of this country is hitting home and hitting home very hard. And that is good. But there will be no grand release— every individual will have to devise his or her own personal method of coming to terms with what has happened.”[2]

Like Russell’s, her book is a testament to the immediate miracle of forgiveness and to the long, slow, messy process of reconciliation. Reconciliation is a wicked problem, in the truest sense. It is not a problem that can be solved overnight, but rather one that must be worked on over a long period of time and will never really be solved.[3] Reconciliation is not a moment but a process that is messy and incomplete. Her book is a reminder that reconciliation does not undo or rewrite the past, but to sit together with the discomfort of it. It is to be quiet before the complexity of it, and to accept its ongoing influence.

These two books immersed me again in the amazing story of South Africa and my own story. Both are intermingled. Both contain miracles and long painful processes. I look forward to the Advance and to being there to share in all of this with my peer group and the larger cohort.

[1] Alec Russell, Bring Me My Machine Gun: The Battle for the Soul of South Africa from Mandela to Zuma, 1st ed (PublicAffairs, 2009), 7.

[2] Antjie Krog, Country of My Skull : Guilt, Sorrow, and the Limits of Forgiveness in the New South Africa (Crown, 2007), 213.

[3] Joseph Bentley PhD and Michael Toth PhD, Exploring Wicked Problems: What They Are and Why They Are Important, Kindle (Bloomington, IN, 2020), 39–41.

6 responses to “Miraculous Moments and Painful Processes”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hi Graham, I know you are deeply moved and apprehensive about going back to South Africa. What do you hope your cohort will pay attention to or walk away with from our time in South Africa?

Christy, I think I’d love our class to walk away with the sense of the beauty and resilience of people and place.

It is one of the most stunning places on the planet The people here have been through so much pain, yet they add hopeful that things will continue to improve.

Graham,

First, thank you for your openness in this blog. Secondly, I love Christy’s question to you. My question, is have you heard echoes of what the white South African said to you about not knowing in relation to Canada and their treatment of Native Americans?

Jeff, I’m not an expert in indigenous studies, but some of the themes are similar.

Graham, thank you for this deeply moving post about your personal experience from then until now. I was in SA two years ago (Jo’burg and Cape Town) and was struck by the ongoing struggles. We met several white Afrikaan women who said the same as your new friend: “We had absolutely no idea. I am deeply ashamed of our history and want to do what I can to make amends.”

We also experienced the rolling blackouts that – as explained to us – are the result of nepotism and corruption in the government. But if your culture was so dependent upon family bonds for so long, it’s challenging to move into a style of government where that’s frowned on (and obviously doesn’t work).

And we met the most amazing people!! They love their country – all of the people we met – and desperately want to heal the open wounds and leftover scars, so they can move forward.

My mentor, Trevor Hudson, is a white, “retired” SA Methodist pastor. He lives just outside Jo’burg. He is gentle, humble, creative, loving, and all that I hope we can all be. South Africa has made him so. May we all become that way.

I look forward to being on this journey with you.

Debbie, thanks for your response. I’m glad you’ve had opportunity to experience South Africa and its people. I’m looking forward to being together with our cohort in Cape Town.