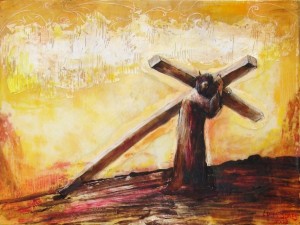

The crucified King still rules the world

I love church history and every year teach a church history intensive in our bible college, so when I saw Tom Holland’s Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind[1] on my reading list, I chose to read it from beginning to end. It is a weighty book, sweeping across millennia of history, weaving together philosophy, theology, politics, and culture, but at its heart is one astonishing truth: the crucifixion of Christ redefined humanity. What the Roman world saw as degradation, the early Christians proclaimed as glory. Holland shows that from this paradox grew the moral and cultural framework of the West, a framework that continues to shape us today even when we deny its source.

What I admire, however, was not only Holland’s telling of Christianity’s triumphs but his honesty about its failures. Undoubtedly, the church has often been compromised, entangled in empire (from Constantine’s conversion), distorted by violence, corrupted by wealth, or scarred by hypocrisy. And yet, Christianity has not disappeared. Against all odds, the faith continues to flourish, and its central paradox remains alive, “God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong” (1 Corinthians 1:27). Holland ends his story there, page 525, and it is the lesson I relate to, as a pastor and a student of leadership.

The Apostle Paul’s metaphor of “jars of clay” (2 Corinthians 4:7) captures the heart of Holland’s writing. Fragile vessels, easily cracked and broken, are entrusted with treasure. Human weakness becomes the stage on which divine power is displayed. Holland, though a secular historian, testifies to this dynamic as he traces Christianity’s rise. The church has demonstrated that its influence does not flow from flawless institutions or impeccable leaders but from a cruciform message that keeps re-emerging, even in times of scandal or decline.[2]

Consider the supposed collapse of Christendom. For centuries, the church wielded immense cultural and political power, often repressively. Yet, when secular thinkers of the Enlightenment turned against the church, they did not abandon its morality. The ideals of liberty, equality, fraternity, and human rights are, as Holland shows, secularised versions of Christian convictions.[3] God’s power persists, even when the jars that hold it are cracked.

The crucifixion was scandalous in its time. Roman elites could not understand worshipping a man executed in shame. Yet the church made this its central proclamation: the true King reigns from a cross. Holland highlights how revolutionary this was. Slaves, women, and the marginalised found dignity because Jesus (the Christian God-Man) identified with them.[4] This inversion of power, where the last are first and the weak are honoured, has remained Christianity’s enduring gift to the world.

But here lies the paradox: the same church that preached the weakness of God often imitated the strength of Caesar. From the crusades to colonialism, from inquisitions to involvement in slavery, the history of Christianity is littered with distortions of its own gospel. Holland refuses to romanticise the church. Yet he also refuses to let its failures erase the fact that its moral essence kept reasserting itself. Even critics of Christianity borrow its assumptions. Nietzsche himself, who declared God dead, could not escape the Christian valuation of compassion, even as he tried to reject it.[5]

Reading Dominion alongside leadership studies brings a striking resonance. Adaptive leadership, as Ronald Heifetz teaches, often emerges not from control but from vulnerability, the willingness to disappoint people at a rate they can absorb, to admit limits, and to face loss.[6] Jim Collins describes “Level 5 Leaders”[7] as those who combine fierce resolve with deep humility. Holland’s thesis shows that such counterintuitive patterns have their deepest roots in the Christian story of weakness as strength.

The Scheins’ Humble Leadership reinforces this, arguing that leadership thrives on openness and relational authenticity, not domination.[8] Leaders who know they are jars of clay can paradoxically carry a greater treasure. In ministry contexts, this requires resisting the temptation to perform strength or perfection and instead embracing the cruciform pattern of servant leadership.

As a teacher of church history, I often tell students: our past is not just a record of glory but a witness to grace. Holland’s book affirms this. The story of Christianity is full of contradiction, light and shadow, saints and sinners, reform and corruption. Yet, through it all, God has chosen to work in history through clay jars. The abolition of slavery, women’s rights, and human dignity all gained their traction through Christians who remembered the radical ethic of the cross, even when the institutional church lagged behind.[9]

For church leaders, Holland’s Dominion offers caution and encouragement. The caution: our power is always fragile and prone to corruption. We are jars of clay, not marble monuments. The encouragement: God still places treasure within us. Even when churches falter, the gospel has a way of rising again.

In my own NPO work on leadership flexibility, I emphasise that leaders must adapt to the seasons their churches are in: growth, stability, crisis, or renewal, to name a few. But beneath all flexibility must lie one constant: the cruciform pattern of weakness. Leaders are at their most powerful when they admit they are jars of clay. God’s power is not diminished by our fragility; it is displayed through it.

Holland concludes Dominion with Paul’s words: “God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong.”[10] That is the story of Christian history. Despite scandal, sin, and excess, Christianity has endured, not because of the strength of its institutions but because of the paradox of its message. In the end, Christianity’s greatest dominion is not its empires or cathedrals but its witness that weakness can bear glory, that clay jars can carry treasure, and that a crucified King still rules the world. The gospel is not fragile, even if the church is. God’s power is still made perfect in weakness. History proves it, and Holland reminds us of it.

[1] Tom Holland, Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind (London: Little, Brown, 2019),

[2] Ibid, 89.

[3] Ibid, 387–388.

[4] N. T. Wright, Paul and the Faithfulness of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2013), 340–41.

[5] Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage, 1989), 86–87

[6] Ronald A. Heifetz, Leadership Without Easy Answers (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 253–54

[7] Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don’t (New York: HarperCollins, 2001), 21.

[8] Edgar H. Schein and Peter A. Schein, Humble Leadership: The Power of Relationships, Openness, and Trust, 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2021), 14–15.

[9] Holland, Dominion, 424.

[10] Ibid, 525.

10 responses to “The crucified King still rules the world”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Glyn,

Great work here mate. Honestly, I love the paradox you highlight. You write, “God’s power persists, even when the jars that hold it are cracked.” And you also write, “The gospel is not fragile, even if the church is.”

Brilliant.

How might you encourage churches to not stress about the fragility of the gospel but instead to have confidence in whom the gospel revolves?

Adam, thanks mate. The gospel doesn’t crack when the jar does. Our role isn’t to stress over fragility but to point to Christ, the treasure within. When leaders and churches feel their limits, it’s not a sign of weakness in the gospel but a reminder that confidence comes from Him, not from how polished or strong we appear. Also, the good news is that a cracked jar can still pour out living water!!

Glynn,

Thanks for your post. I agree with Adam’s comments regarding your statement about cracked jars. I also appreciate that you wrote ““God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong” (1 Corinthians 1:27). Holland ends his story there, page 525, and it is the lesson I relate to, as a pastor and a student of leadership.” I wonder whether in your own life or others, how have you witnessed God using those we would least expect to do something absolutely amazing?

Thanks so much for this encouragement Geoff. Honestly, I’ve seen God do this again and again, in Scripture, history, and ministry life. One of the most vivid examples was watching a young believer, from an overlooked background by most and unsure of their own gifting, step into leadership during a crisis and carry a whole group with wisdom far beyond their years. It reminded me that God delights in choosing those we’d least expect, not to showcase their strength but to display His. The “jars of clay” image is important, ordinary people being the very vessels through which God does something extraordinary. It’s humbling as a leader and hopeful for the church.

Great post Glynn. I especially appreciate your words, “Christianity’s greatest dominion is not its empires or cathedrals but its witness that weakness can bear glory, that clay jars can carry treasure, and that a crucified King still rules the world.” As we prepare for our time in Cape Town, what intersections do you see with the Church and the reconciliation movement in post-apartheid S.A.?

Thank you Ryan. In Cape Town, the intersection seems connected: reconciliation is itself a cruciform act, where weakness becomes strength and where fractured communities can carry treasure. Post-apartheid South Africa still bears scars, but the church’s witness is powerful when it refuses to lean on empire, dominance, or image, and instead embodies the cross, humility, repentance, forgiveness, and restored dignity. The jars may be cracked, but that is exactly how the light of Christ shines through to heal and reconcile.

Glyn, Thank you for the great post. I hope you will one day use it as a sermon or lesson at the Bible school. I love that you brought in the clay jars analogy. In your response to Adam you say, “the good news is that a cracked jar can still pour out living water.” In human brokenness, we see the Gospel take deep root —the persecuted church is one area that comes to mind. What may help Western Church culture embrace this idea of brokenness and humility, especially for its leaders?

Thank you Kari. I think what will help the Western church most is recovering the truth that weakness isn’t something to be managed away but something God actually works through. Our culture celebrates image, strength, and success, but leaders who model vulnerability, repentance, and dependence on Christ create space for the gospel to take deep root. When pastors admit they are jars of clay rather than monuments of perfection, it shifts the culture from performance to presence, and that humility may be the very thing that allows living water to flow again.

I love this sweeping post Glyn. And I appreciate the other voices you bring in to highlight how humility and weakness are actually the ways of God.

I’m wondering what your personal application from this book might be? Either a recognition of your own weakness or humility, or a place where you know you need God’s grace to demonstrate that more?

Thank you Debbie. For me, one of the biggest personal applications is remembering that leadership isn’t about proving strength but staying dependent on God’s grace. I often feel the pull to project confidence and certainty, especially in high-stakes moments, yet the reminder of being a “jar of clay” helps me admit limits and lean into God’s power instead of my own. One area I continually need His grace is in holding the tension between leading boldly and leading humbly, recognising that real authority comes when I’m willing to serve, confess weakness, and let Christ’s strength be the one on display.