If You Eat Quiche, Can You Wear A Scarf?

“Real men don’t eat quiche” is a phrase from the 1982 book Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche by Bruce Feirstein.[1] The book is a satire of masculine stereotypes. In a clever tongue-in-cheek approach, Feirstein explained what was acceptably “masculine” and “feminine” behavior according to the era’s societal standards. For real men, quiche was, apparently, a no-go, along with expressing emotions and being sensitive. Instead, real men ate meat, took risks, participated in “masculine” activities, and wore only rugged clothes, which didn’t include scarves. Being a child of th e 80s with my primary role models appearing in shows like The Duke’s of Hazzard, The A-Team, and He-Man, you can understand my internal conflict and confusion when my kids gave me a scarf this past Christmas…and I liked it! It’s funny how the brain works sometimes. While not a neuroscientist, David Rock presents helpful insight into how our brains work in a very approachable way in his book Your Brain At Work.[2] He introduces many practical thinking hacks that are immediately applicable (even while writing this blog article). In this post, I will look at two key insights and a couple of practical considerations from this book.

e 80s with my primary role models appearing in shows like The Duke’s of Hazzard, The A-Team, and He-Man, you can understand my internal conflict and confusion when my kids gave me a scarf this past Christmas…and I liked it! It’s funny how the brain works sometimes. While not a neuroscientist, David Rock presents helpful insight into how our brains work in a very approachable way in his book Your Brain At Work.[2] He introduces many practical thinking hacks that are immediately applicable (even while writing this blog article). In this post, I will look at two key insights and a couple of practical considerations from this book.

Thinking Smarter, Not Harder – Prioritize

While thinking is a renewable resource, our ability to think well is limited. According to Rock, with insights from neuroscience, there are practical ways to conserve energy consumed by thinking. Rock explains, “Conscious mental activities chew up metabolic resources, the fuel in your blood, significantly faster than automatic brain functions such as keeping your heart beating or your lungs breathing.”[3] This explains the feeling of exhaustion after a long day of emails, meetings, strategic planning, and problem-solving. We must conserve the brain’s energy for the most critical tasks to minimize exhaustion and maximize our thinking effectiveness. An essential step in this conservation effort is to “Prioritize Prioritizing.” Rock argues that prioritizing is one of the most brain energy-draining activities.[4] If we give ourselves to other mental activities, we may not have the energy to prioritize, which sends us down an unproductive path. Prioritizing has broad implications but is easier said than done. The notifications and red bubbles on my phone assault me the moment I awake. The desire to open my email and scroll through the inbox is a real temptation. It will require discipline to put that off until I have prioritized the day.

Consideration: I must consider how I can avoid the temptation to engage in thinking tasks that need to wait. This relates to what Rock later addresses with external and internal distractions in the book, which, if space allowed, I would explore further.

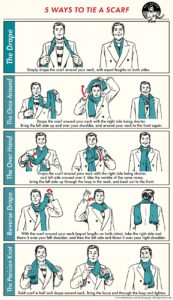

How to Wear a SCARF

Anot her critical insight Rock offers relates to our interaction and leadership of others. Understanding how our approach triggers certain brain activities in others is very important. Key to this understanding is how emotions activate the brain and create specific responses. The brain is designed to help us survive and naturally identifies threats and rewards. Our brain gets us to move instinctively away from threats and toward rewards. For instance, one of the subconscious activities the brain is always running has to do with status, specifically, trying to maintain a high status compared to others. Rock states, “You can elevate your status by finding a way to feel smarter, funnier, healthier, richer, more righteous, more organized, fitter, or stronger, or by beating other people at just about anything at all. The key is to find a “niche” where you feel you are “above” others.”[5] This means we naturally move away from things that threaten our status and toward things that secure or have the potential to elevate our status. In total, Rock identifies five domains of social experience that our brain treats the same as survival issues. These domains form a model, which he calls the SCARF model, which stands for Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness.[6] When a person perceives a threat in one of these areas, the brain triggers a survival response. This response involves a combination of chemical, hormonal, and emotional responses, lowering a person’s ability to reason clearly, learn new things, or remain calm.

her critical insight Rock offers relates to our interaction and leadership of others. Understanding how our approach triggers certain brain activities in others is very important. Key to this understanding is how emotions activate the brain and create specific responses. The brain is designed to help us survive and naturally identifies threats and rewards. Our brain gets us to move instinctively away from threats and toward rewards. For instance, one of the subconscious activities the brain is always running has to do with status, specifically, trying to maintain a high status compared to others. Rock states, “You can elevate your status by finding a way to feel smarter, funnier, healthier, richer, more righteous, more organized, fitter, or stronger, or by beating other people at just about anything at all. The key is to find a “niche” where you feel you are “above” others.”[5] This means we naturally move away from things that threaten our status and toward things that secure or have the potential to elevate our status. In total, Rock identifies five domains of social experience that our brain treats the same as survival issues. These domains form a model, which he calls the SCARF model, which stands for Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness.[6] When a person perceives a threat in one of these areas, the brain triggers a survival response. This response involves a combination of chemical, hormonal, and emotional responses, lowering a person’s ability to reason clearly, learn new things, or remain calm.

Consideration: I have been working on the performance review process we will use as a staff team, and I want to explore how we can apply the SCARF model to the review process. How can we help our team notice what is good about themselves and raise their status? How can we make our expectations clear, increasing their certainty? How can we empower them to make decisions, increasing their autonomy? How can we create space to connect with them more personally, increasing their relatedness? How can we ensure we are being considerate and fair in our treatment?

[1 ] Bruce Feirstein, Real Men Don’t Eat Quiche, (New York: Pocket Books, 1982).

[2] David Rock, You Brain At Work, (New York: Harper Collins, 2009).

[3] David Rock, You Brain At Work, 10.

[4] David Rock, Your Brain At Work, 13.

[5] David Rock, Your Brain At Work, 132.

[6] David Rock, Your Brain At Work, 134.

8 responses to “If You Eat Quiche, Can You Wear A Scarf?”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hi Chad, thanks for your post. Rock describes how we are by nature trying to raise in status, especially compared to others. I understand this tendency and have experienced it often – but I’m unsure of how to interpret it.

As a pastor, do you consider this to be part of our survival instincts or part of our sinful nature?

That is a great question. I think it’s a survival mechanism that resulted from the fall. However, I am not sure if it is always sinful.

Chad,

You mention some practical thinking hacks that even helped you write the blog post. Your post is great, and I appreciate the tie in to the scarf pnuemonic. So, what are one or two of the practical hacks that helped you write?

Adam, thanks for the question. The primary hack used in writing and most of the doctoral work for me was the recognition of internal and external distractions. Minimizing these and doing certain thinking exercises first (prioritizing) allowed me to see how I could better leverage my writing time.

Chad,

Glad you like your scarf, wear it while you can. I teach an interviewing and documentation class and students have to record mock interviews which I then critique. The other day, first thing in the morning, while my brain was fresh, I reviewed the videos and was fairly critical, even the best videos received feedback about what could have been done differently. Later in the day at the start of class, I informed students that I had reviewed their videos and had given helpful feedback. But then I told the students that the videos were more of a reflection of me and my ability to convey information to them. I then proceeded to clarify to them things that I thought I had communicated but may have missed. I did this to ensure the students did not feel attacked by my comments. I hope the students appreciated this.

As a pastor how do you manage to prioritize your day/week to accomplish what you need to (sermon prep) when, I’m guessing, other attention seeking situations present themselves. Do you have any firm rules you use to govern your day?

Thanks for this helpful article Chad. I would ask you all the questions you’ve posed in your second set for Considerations. 😉 But I’ll just ask one: Which of those questions do you think is the most important, that might help set up all the others? (Prioritization…)

Jeff, thank you for taking the time to read my post and share your experience. To answer your question, I have a few firm time blocks established throughout my week that are guarded. Besides that, I am pretty open.

Hi Chad,

I learn so much from reading other people’s posts because we all seem to gravitate to different things. You highlighted a quote, “Conscious mental activities chew up metabolic resources, the fuel in your blood, significantly faster than automatic brain functions such as keeping your heart beating or your lungs breathing.”

This made me thing about the aging process and how our brains slow down and maintaining cognitive function becomes a priority. One of the things we do in our house is to do mental exercises to help in that — being in school is part of it, but also using our less dominant hand to do activities such as brushing your teeth. You get the idea.

Since you mentioned the SCARF method, if I were to ask one of your staff how to answer those questions about you, what do you think they might say?