The Evangelical – Then and Now

The Christian church throughout history has been defined in the cultural context of each era in which she has existed. As we move deeper into the twenty-first century, the church must define herself in the context of a post-Christendom and a post-modern era. I believe those who are leaders realize the difficult task to equip the church in this present era. I know that in my small world of participation and influence, the church is in decline.

Dave Male expresses a similar concern for the church in the United Kingdom (U.K.) in his book, Pioneering Leadership: Disturbing the Status Quo? Male states, “[W]e have one generation in the UK to turn the church around, or the decline we are facing will be of such momentum that humanly speaking, with massively dwindling resources, there will be little we can do.”[1] He provides startling and alarming statistics that project attendance in the Anglican Church (evangelical) to decline 90% (from 1.2 million to 125,000) over the next fifty years.[2]

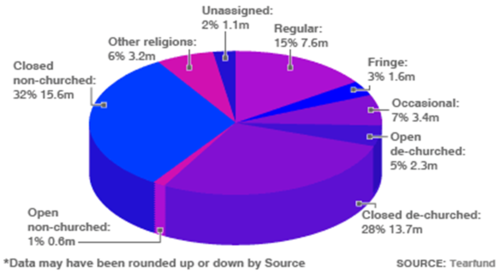

Male indicates the problem is intensified with less than 20% of the population in the U.K. presently regular in church attendance. A majority, (66%), “are unreceptive and closed to attending church; churchgoing is simply not on their agenda.”[3] In this context, the church must develop imaginary leaders skilled and trained “to navigate this new missionary agenda of our times … to discover the kingdom’s innovatory practices, appropriate to our particular context.”[4]The key, Male would indicate, is to develop pioneering leaders that feel the urgency of the challenge confronting the twenty-first century church.

Understanding how we got to where we are at this context in history can be helpful in assessing who we are and provide some markers for how we might meet the challenge of moving forward. In his book, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s, D. W. Bebbington, gives an inspiring and illuminating history of the Evangelical church movement in the U.K. Written in historical genre, the book provides a huge volume of facts presented in a readable style so as to illuminate the historical context of Evangelicalism. Although on a different stage of history, I am struck by the similarity of the transition confronting the church in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The comparison represents different cultures, philosophies, and social environments, however, the “evangelical characteristics”[5]are the same.

Bebbington indicates that there are four qualities or identifying marks of “Evangelical religion: conversionism, the belief that lives need to be changed; activism, the expression of the gospel in effort; biblicism, a particular regard for the Bible; and what may be called crucicentrism, a stress on the sacrifice of Christ on the cross.”[6]These four (quadrilateral) identifying marks express evangelical theology and practice. Bebbington traces the historical implementation of each of these characteristics across two hundred and fifty years and notes the manner in which they unify Evangelicalism. Of course, there are divergent interpretation and application across the different Evangelical “strains.” Historically, the different characteristics had greater or lesser emphases depending on the theology and were expressed differently by the different strains of Evangelicalism. These characteristics “formed a permanent deposit of faith”[7]through generations and continue yet until today.

Each of these characteristics are discussed by Bebbington and the relevance for the twenty-first century Evangelical is evident. I will discuss only a couple here. The centrality of the cross and the doctrine of atonement was an essential part of Evangelicalism and remains so today. It gives rise to many fundamental questions of the Christian faith. What are the implications for Christian living? Who is included – for whom did Christ die? Was the crucifixion a “victory” over evil powers or a substitution for humanity’s sin? The dialogue continues yet today.[8]

Conversion remains as a central element of Evangelical teaching and practice. The culture is different as the rational age that elevated the individual in an age of reason has been replaced by the plurality of individual choice by virtue of tolerance. Yet throughout history and until the present, reconciliation between God and creation remains an individual issue. Often Bebbington brings insight and lightness with his antidotes. He tells the story of the clergyman who was “converted by his own sermon!”[9] In the same manner, activism continues as a leading characteristic of Evangelicals. There was urgency in preaching and evangelizing. Often circuit clergymen would ride many miles, attend multiple worship services, prayer meetings and Bible studies in one day.[10] Again, by way of antidote, Bebbington tells the story of Adam Clarke, the great Wesleyan theologian and Bible scholar, giving up his tea and coffee times at John Wesley’s urging in order to apply himself in study; “consequently [he] saved several whole years of time over the rest of his life for devotion to Christian scholarship.”[11] I have already noted earlier the need to sense the urgency in the present era and to be diligent and committed in the practice of the Christian faith, evangelization and mission.

There are many other significant applications and administration of Evangelicalism that we can apply to our current theology and practice. The presence of women in ministry and the assurance of salvation remain as central in theology and practice. I loved this book; again my only regret is I need another week to study and reflect on the reading. I spent too much time in the footnotes and the internal bibliography. I found several books cited by Bebbington and downloaded two of the original sources that Bebbington provided. I will include the reference here:

A landmark publication written in 1828; The Unconditional Freeness of the Gospel, by Thomas Erskine.[12]

A Puritan works of casuistry designed to deal precisely with fear written in 1669; Precious Remedies against Satan’s Devices, Thomas Brooks.[13]

[1] Dave Male, Pioneering Leadership: Disturbing the Status mQuo? (Cambridge, UK: Grove Boojs LTD, 2013), 3.

[2] Ibid.

[3] David Male, see presentation at: “GFES London Advance – 2013,” Church Unplugged, http://davemale.typepad.com/churchunplugged/2013/09/george-fox-london-september-28th.html (accessed 2/6/2014)

[4] Male, Pioneering, Ibid.,7.

[5] D. W. Bebbington, Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (London, UK: Routledge, 1989, Kindle), 2.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., 271.

[8] See for an example: James Beilby and Paul R. Eddy, eds., The Nature of the Atonement: Four Views (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006)

[9] Bebbington, Ibid., 6, emphases mine.

[10] Ibid., 10.

[11] Ibid., 11.

[12] Thomas Erskine, The Unconditional freeness of the Gospel (Edinburgh, UK: Edmonston and Douglas, 1873), https://ia600808.us.archive.org/23/items/unconditionalfre00ersk/unconditionalfre00ersk.pdf, (Accessed: Feb. 6,2014)

[13] Thomas Brooks, Precious Remedies against Satan’s Devices (Unknow original pub.: 1669), http://www.preachtheword.com/bookstore/remedies.pdf or HTML, http://www.gracegems.org/Brooks/precious_remedies_against_satan.htm, (Accessed: Feb. 6, 2014)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.