Fear Not: Intersections and Opportunities in Postmodernism

Up front let me acknowledge that I am a middle-aged, caucasian, female, Christian from Canada. This is inescapably the subjective space from which I encounter the world. I recognize that I have inherited privilege and power because of these identities. These details don’t solely define me and there are many more that would offer more insight, but if put in a room with others who self-identified in a similar way, we would already have a lot more in common than these identities. Embracing that I cannot interpret the world from outside this lens has led me to be curious about the lenses that others interpret the world through and to be humble enough to know that because I come from a particular context, with a particular identity, I cannot claim to be an authority of how people from other contexts might experience and interpret the world. This has been a gift from postmodern thought to my ministry.

I fell in love with Jesus as a child, with Kant, Hegel, Derrida and Foucault in my undergraduate and with Greek and New Testament Theology in Seminary. Fortunately literary close readings were good preparation for exegetical approaches to Biblical study. Through my study, I persistently brought two questions with me: How might this help me love God more? How might this help me love others more? Perhaps it is this starting point that has permitted me to see value and opportunity in postmodern thought.

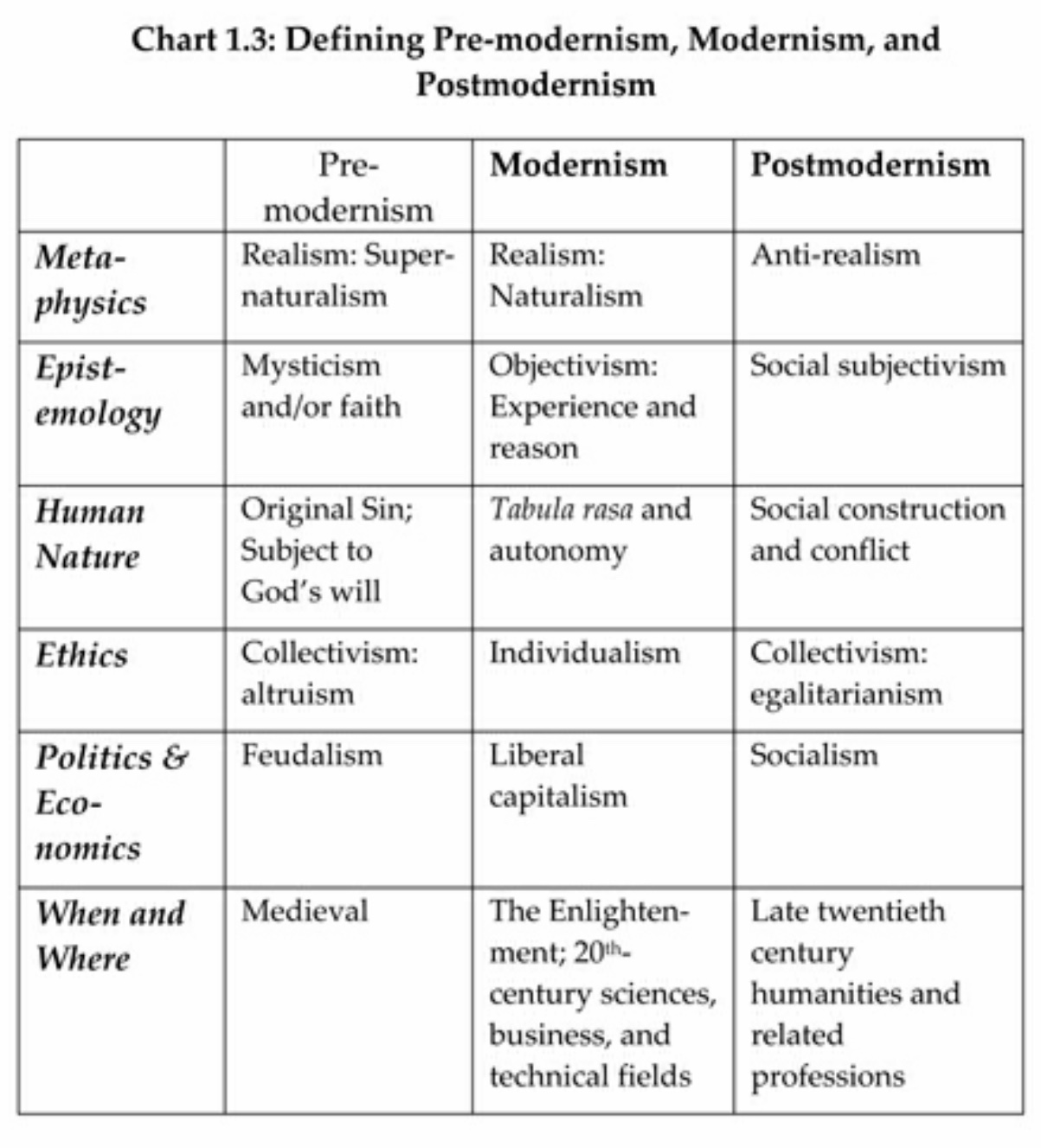

Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault did not seek to highlight the value and opportunity within this school of thought, but rather to portray it as the result of the “anger and despair” of failed counter-enlightenment and socialist experiments.[1] This is an unsurprising approach from Canadian-American philosopher Stephen R. C. Hicks, who teaches at Rockford University. (Incidentally we share an Alma mater in the University of Guelph where he received both his B.A. and M.A. Had he attended fifteen years later we may have been classmates.) As a Senior Scholar for The Atlas Society,[2] Hicks brings an analytic objectivist critique to Postmodern thought. Ayn Rand embodied this perspective in the fictional protagonist of The Fountainhead, Howard Roark. Roark is characterized by individualism, reason and innovation and is set in contrast to the altruistic character Peter Keating. Rand uses Keating to demonstrate that selflessness and sacrifice are contra to flourishing and are harmful to humanity.[3] It seemed evident in my reading that Keating was meant to stand in for Christianity. All that to say, while Hicks critique has validity, his Randian worldview does not suggest a Christian perspective. Let me thus offer some of the opportunities of postmodern thought.

First, it’s critique of individualism recognizes the value of collective identity. Whereas the premodern ethic was altruism, with a paternal benefactor extending generosity to the vulnerable, the postmodern ethic asks that we work to recognize the equal value of the vulnerable and treat them as such. Both the pre-modern and post-modern ethic has scriptural precedent.

Second, the proposition that social hierarchies are constructions and are vulnerable to pride and abuse of power by authority figures has a natural alignment to the Protestant reformation. Whereas the pre-modern mindset upheld that Ecclesiological hierarchies were instituted by God, postmodernism critiques institutional hierarchies but embraces local, shared leadership and has an openness to the grassroots expressions of church that are reminiscent of the first two centuries of the church.

Third, the critique of pure reason allows space for mystery and transcendence to re-emerge. What is knowable is only knowable as a transaction between an object and the subject. However it might be possible to invite a postmodern thinker to embrace the notion that the Holy Spirit is present in the interaction such that the object is revealed to the subject. So while the subject continues to experience the world solely from their subjective position, there is a Mediator within this construction of meaning. What could otherwise spiral into absolute relativism becomes a relational disclosure.

Finally, relativism creates space for relationalism, that is where all things are in relationship with an Absolute—that is God. I agree with Shleirmacher in that “[l]imiting reason is thus the essence of religious piety—for it makes possible a fully-entered-into feeling of dependence and orientation toward that being upon which one is absolutely dependent. That being is of course God.”[4] Derrida did not deny an absolute truth, he denied our ability to fully access absolute truth. I’ve always found this resounds well in Christianity. I would suggest that God is in fact the only Absolute Truth, but that God is not fully knowable to His creation. Instead I would argue that God is sufficiently knowable for us to be in relationship with. My task then as a Christian ministering in a postmodern context is not to (operating out of my privilege and power) pour my knowledge of God into another person, but instead share my story of experience as a gesture towards the Absolute Truth, that is God.

Experiments in expressions of church can be appealing to those influenced by postmodernity. Perhaps think of it as deconstructed church. Len Sweet suggests this perspective: keep it Experiential, Participatory, Image-Centred and Connected[5]. Create space for their experiences and celebrate the unique perspective each will bring out of distinct subjectivities. If it is a philosophy that you have found particularly unsettling, might I offer these questions to hold in the back of the mind: How might my relationship with this person lead me to love God more? How might I love this person better in Jesus’ name?

[1] Stephen R. C. Hicks, Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault (Expanded Edition). (China: Okham’s Razor Publishing, 2014) Kindle loc 4227.

[2] “Stephen Hicks,” The Atlas Society, accessed February 6, 2020, https://atlassociety.org/about-us/staff/21-stephen-hicks)

[3] George H. Smith, “Ayn Rand and Altruism, Part 3,” Libertarianism.org, November 6, 2012, https://www.libertarianism.org/publications/essays/excursions/ayn-rand-altruism-part-3)

[4] Shleirmacher as quoted by Stephen R. C. Hicks in Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault (Expanded Edition). (China: Okham’s Razor Publishing, 2014) Kindle loc 1376.

[5] Leonard Sweet, Postmodern Pilgrims: First Century Passion for the Twenty-first Century World. (Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Publishing Group, 2000).

7 responses to “Fear Not: Intersections and Opportunities in Postmodernism”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Howdy. These are interesting questions. You’re going to love (not) reading Peterson in a few weeks, because he literally tears apart all forms of pre and postmodern views of the world from a psychological viewpoint. If you strip away politics, religion and academics we are left with raw human power – his point will loosely be that postmodern socialism is little more than the exersion of a new form of control over others – its a dangerous shift of institutional power. On another point, I have often wondered if there is a correlation between postmodernism and the expansion of pentecostalism over the last 40 years – a connection with Taylors transcendence rediscovery. All these new readings are going to drag out our epistemological differences – so exciting.

Hi Digby. I don’t think we have to go to Peterson to connect postmodernism to the will to power and control over others. I thought Hicks did a fine job of doing that for us already. The unholy trinity of Marx, Mercuse and Mao, if anything taught us that socialism/communism leads to death. I actually learned a new term reading Hicks—“democide.” It’s not even in the common dictionaries. It was coined in the early 1990 when a researcher tried to tabulate all the atrocities perpetuated by statist governments such as Russia and China. Its leaders, Stalin and Mao killed hundreds of millions of their own people. I compared the numbers of deaths between what socialist/communist countries and democratic ones in terms of democide. It’s unbelievable. The ratio is like 1:150.

Foucault in the end of “The Order of Things” talks about man being a recent invention and that he will be “erased.” That was his hope. Scary stuff.

Peterson and Hicks – a double whammy. Foucault comes across a kind of apocalyptic dispensationalist for the non religious.

Jenn, I appreciate that you have identified great opportunities for the church in the midst of the confusion that postmodernism seems to create.

Thank you, Jenn, for not only providing an interpretation of Hicks and postmodernism, but also sharing how these theories can be used in winning souls to Christ. I do think it is important to be able to minister to all those in need.

I am happy that you identify yourself positively with Postmodernism in your Christian journey. I find it hard to connect with this for real especially from an African point of view. All the way from Enlightenment and postmodernism, it has been power and control. As much as postmodernism is trying to demystify the enlightenment, it is not even better although it brings out the element of thinking externally rather than internally.

Jenn, thanks for amalgamating all that into a usable set of questions. I appreciate your perspective.