Domestic Commodification 101

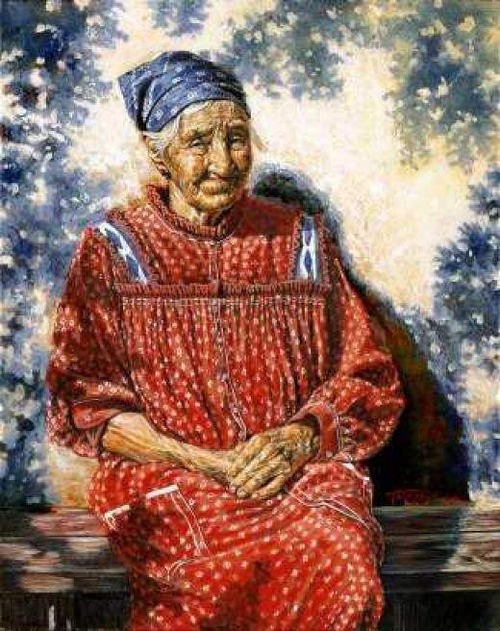

In our reading for this week[1], Vincent J. Miller, Associate Professor of Theology at Georgetown University, writes about consumer culture. Unlike some of our other readings, Miller offers some suggestions/solutions for the Church to consider on how to flourish in the midst of the consumeristic bombardment experienced in the world around us. One of his suggestions for countering commodification is to consider the importance of what he calls, The Craft Ideal.[2] Miller discusses the history of commodified objects and how these compare to handcrafted objects. His main point here is that when one understands the time and effort that goes into making a product, such as a quilt that takes over 200 hours to complete, compared to a commodified (machine-made) product, one will come to a conclusion that commodified goods (particularly those that are made in developing societies under inhumane working conditions) are suspect. Should we support such products? Or would this be an immoral purchase? Miller writes, “Consumeristic habits of use and engagement are not simply about things; they are about how we relate to things.”[3] So how do we as Christians relate to things, particularly to material things? How do we live in a consumer culture, a commodified culture, in such a way that we do not give our nod of approval to waste, neglect, and injustice? How do religious organizations live in ways that honor the Kingdom of God? These are complicated but important questions – none of which has an easy answer.

While living in Cairo, Egypt, I would often visit a Christian orphanage on Fridays. I would bring my guitar and sing songs with the children. I was also there to learn the culture and language, to teach some English, and to act like a true believer. These were good days. In the summer of 1990, I was invited to speak in Alexandria at a retreat sponsored by the orphanage. There were about 100 children and youth present, as well as the orphanage staff. I was the only non-Egyptian at the retreat. One of my messages was on the uniqueness of each individual; I spoke on the creation story in Genesis and related how God spoke into existence all of creation, with one exception – human beings. Here was my central point: “Because humans were created by the hands of God, they were unique, special – handmade.” It was a great message, or so I thought. In the final meeting, the leader of the orphanage called me to the front of the room to thank me for coming. He then presented me with a small and beautiful Egyptian rug with these words, “Thank you for coming to our retreat. In Egypt, we do not value handmade objects as much as machine-made objects. The better and more expensive goods are not handmade. I would like to present you with this gift to remember us. I would have bought a machine-made rug for you, but remembering your sermon, I bought one that was handmade.” We had a good laugh about this. It was a memorable moment. I had made a cultural blunder, not the first and not the last. Different cultures value things differently. So which is better, a machine-made product or a handmade product?

In a typical urban Egyptian “home,” families live in high-rise buildings where the family rents one or more “flats” (apartments), depending on the size of the family. Being a predominately patriarchal society, the son’s family lives in the same building as his parents. If there are several children, there are several flats (at least if the family is wealthy enough to afford it). This hybrid extended family system is common; it is a cultural practice – it is normal behavior. Not so in Western nations. Particularly in America, the household patterns revolve around the nuclear family. Extended family life is rare these days, even in rural settings. The nuclear family is now the norm; it is the American standard. As different as these two systems are, they are also similar in one major way; they are both part of a “consumer culture.” Both American and Egyptian families exchange cash for goods and both are dependent on the economic system to keep their lifestyles afloat. Is this a problem? Yes and no. But it is the reality of modern life. So, which of the family style is better in regard health and permanence? Certainly there are strengths and weaknesses to both models, and one could come up with different answers, depending on who was asks. However, for the sake of this discussion, I would like to table this matter for now. Rather, I would like to ask a different question. Has family life always been this way?

Actually, for both cultures, it was not always this way. In fact, it was not that long ago that most people lived in rural settings, on small farms, and both American and Egyptian families lived in traditional extended families. The extended family that lived off the land was quite different from the modern nuclear family. Food was not bought; it was grown. Clothing was not purchased; it was handmade by the family. And grandma did not move to a convalescent hospital; she had a permanent place in the extended family unit. Miller points out that although the extended family did require some consumption, this was “enmeshed in a complicated division among extended family.”[4] That all changed with the establishment of the American single-family home. With this development came the complete acceptance of the modern nuclear family that depended on wages to support its “consumption-centered lifestyle.”[5] Vincent Miller writes, “Here is the birth of ‘normal’ consumption in the United States, where simply living involves owning and maintaining a home, regular improvements to maintain its market value, owning one and then two cars for transportation to work, shopping, and so on.”[6] Add to this a large mortgage, and you are a full-blown American Dream consumer – but with no more farm, no more homemade clothes, and no more grandma! No one could describe this sociological and economic event as authoritatively and well as Wendell Barry. Barry writes[7]:

The small family farm is one of the last places—where men and women (and girls and boys, too) can answer that call to be an artist, to learn to give love to the work of their hands. It is one of the last places where the maker—and some farmers still do talk about “making the crops” — is responsible, from start to finish, for the thing made. This certainly is a spiritual value, but it is not for that reason an impractical or uneconomic one. In fact, from the exercise of this responsibility, this giving of love to the work of the hands, the farmer, the farm, the consumer, and the nation all stand to gain in the most practical ways: They gain the means of life, the goodness of food, and the longevity and dependability of the sources of food, both natural and cultural. The proper answer to the spiritual calling becomes, in turn, the proper fulfillment of physical need…

The family farm is failing because the pattern it belongs to is failing, and the principal reason for this failure is the universal adoption, by our people and our leaders alike, of industrial values, which are based on three assumptions:

1. That value equals price — that the value of a farm, for example, is whatever it would bring on sale, because both a place and its price are “assets.” There is no essential difference between farming and selling a farm.

2. That all relations are mechanical. That a farm, for example, can be used like a factory, because there is no essential difference between a farm and a factory.

3. That the sufficient and definitive human motive is competitiveness — that a community, for example, can be treated like a resource or a market, because there is no difference between a community and a resource or a market…Here we come to the heart of the matter — the absolute divorce that the industrial economy has achieved between itself and all ideals and standards outside itself. It does this, of course, by arrogating to itself the status of primary reality. Once that is established, all its ties to principles of morality, religion, or government necessarily fall in place.

But a culture disintegrates when its economy disconnects from its government, morality, and religion. If we are dismembered in our economic life, how can we be members in our communal and spiritual life? We assume that we can have an exploitive, ruthlessly competitive, profit-for-profit’s-sake economy, and yet remain a decent and a democratic nation, as we still apparently wish to think ourselves. This simply means that our highest principles and standards have no practical force or influence and are reduced merely to talk…

As a nation, then, we are not very religious and not very democratic, and that is why we have been destroying the family farm for the last forty years — along with other small local economic enterprises of all kinds. We have been willing for millions of people to be condemned to failure and dispossession by the workings of an economy utterly indifferent to any claims they may have had either as children of God or as citizens of a democracy. “That’s the way a dynamic economy works,” we have said. We have said, “Get big or get out.” We have said, “Adapt or die.” And we have washed our hands of them…

Wow! Barry’s piece takes me back to an earlier question, “Which of the household models is best for a family’s health and permanence?” I think I know Wendell Barry’s answer. I also know that the “good-old-days” are probably a myth; however, there is certainly room for a backward glance once in a while. I sometimes long for the dirt of the farm under my nails and for knitted sweaters, but what I miss most is Grandma. How about you?

[1] Vincent J. Miller. Consuming Religion: Christian Faith and Practice in a Consumer Culture (New York: Continuum, 2003)

[2] Ibid., 186.

[3] Ibid., 186.

[4] Ibid., 46.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Wendell Barry. Excerpts from Home Economics (1987) Retrieved from https://ukiahcommunityblog.wordpress.com/2010/04/16/wendell-berry-home-economics/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.